4321 SRAM

Published:

Now you are at the next stage of 4321: the mighty SRAM

Many parts of this PS can be done in parallel. Get your teammate to work!

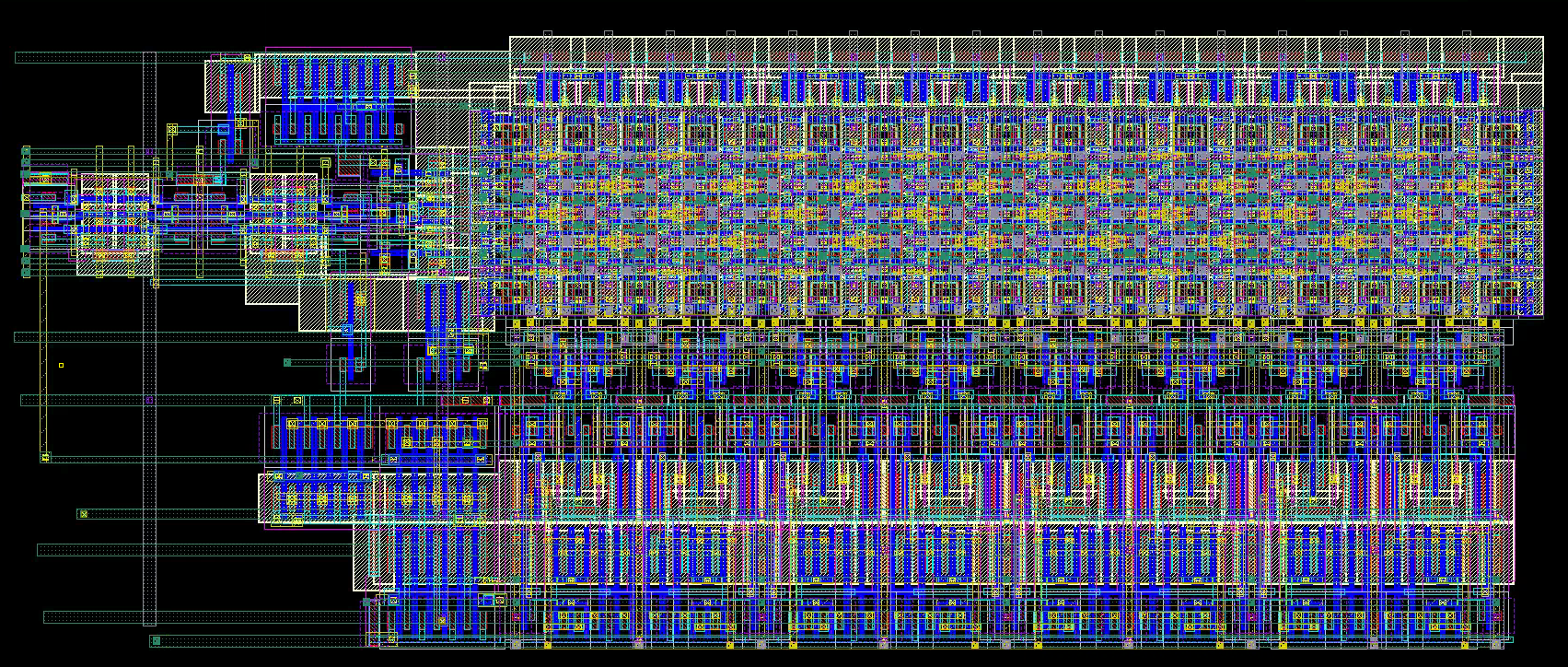

Floorplan

There are a lot of ways to floorplan the SRAM. You don’t have to, but it would be really nice if all the peripherals match the width of the SRAM array.

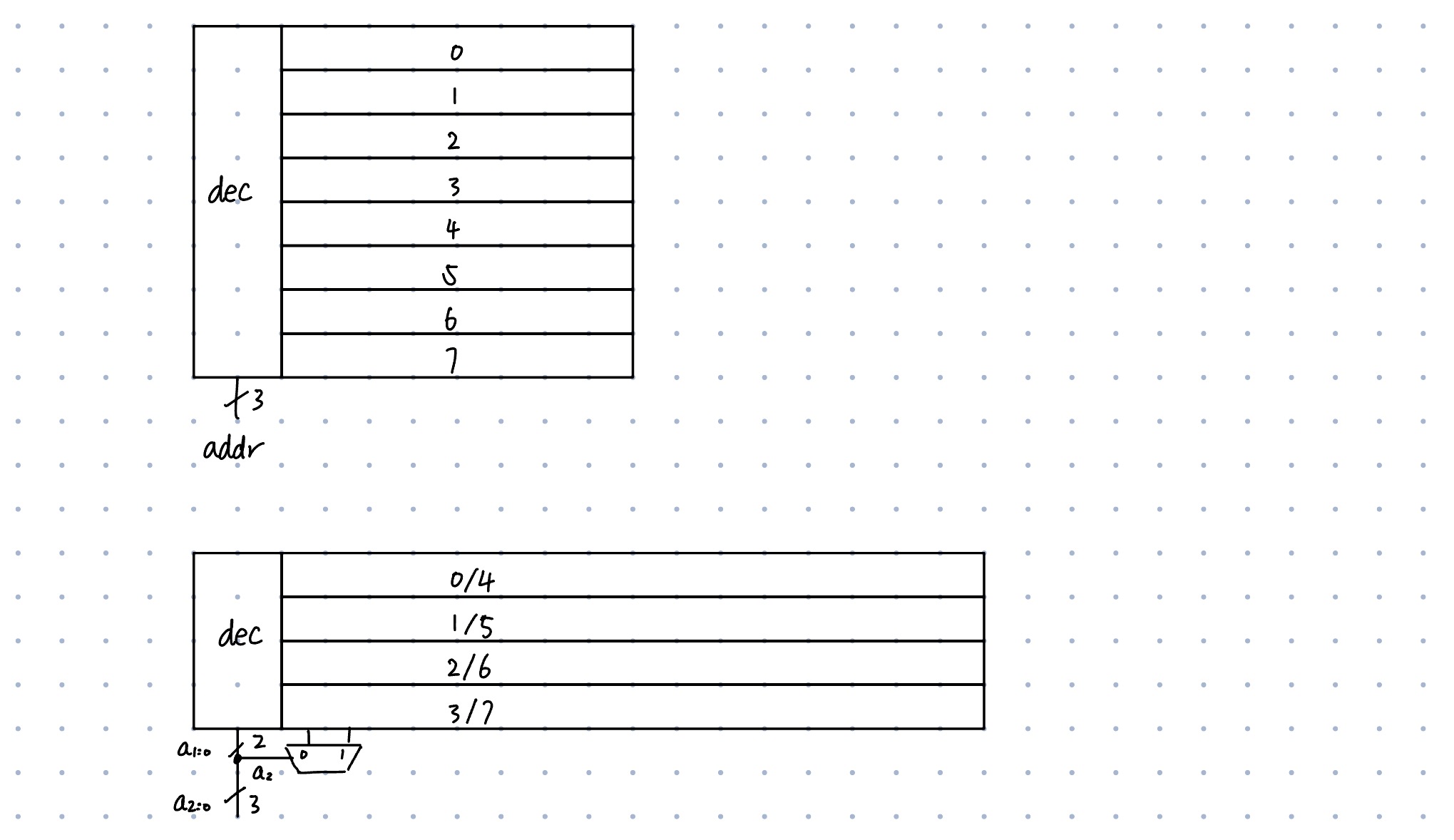

Because the SRAM cell is extremely dense, we use column multiplexing, sharing one set of R/W circuitry for each two adjacent columns

- Logically, the array is 8x8. (8 wordlines, 3-bit addresses; 8 bits for

iobus) - Physically, we lay it out as 4x16 (16 bitline pairs), where each pair of the adjacent physical column map to one logical column

- Essentially, we shift a dimension from rows into columns to the column: one wordline address bit becomes the column MUX select.

SRAM Array

Throughout this article, an array written as \(x\times y\) always mean row \(\times\) column

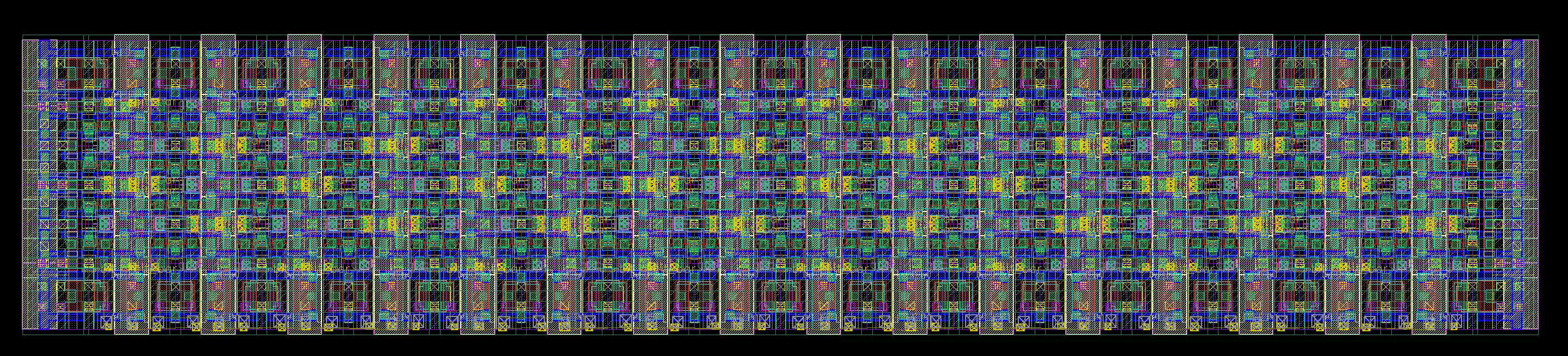

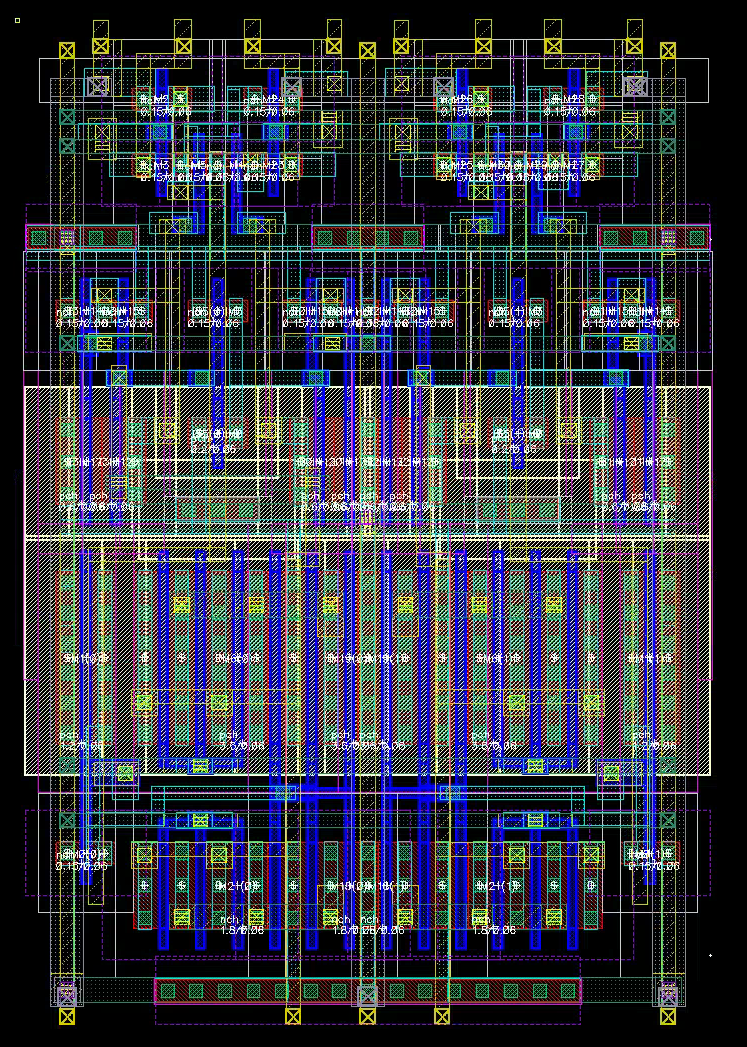

8x8 Layout

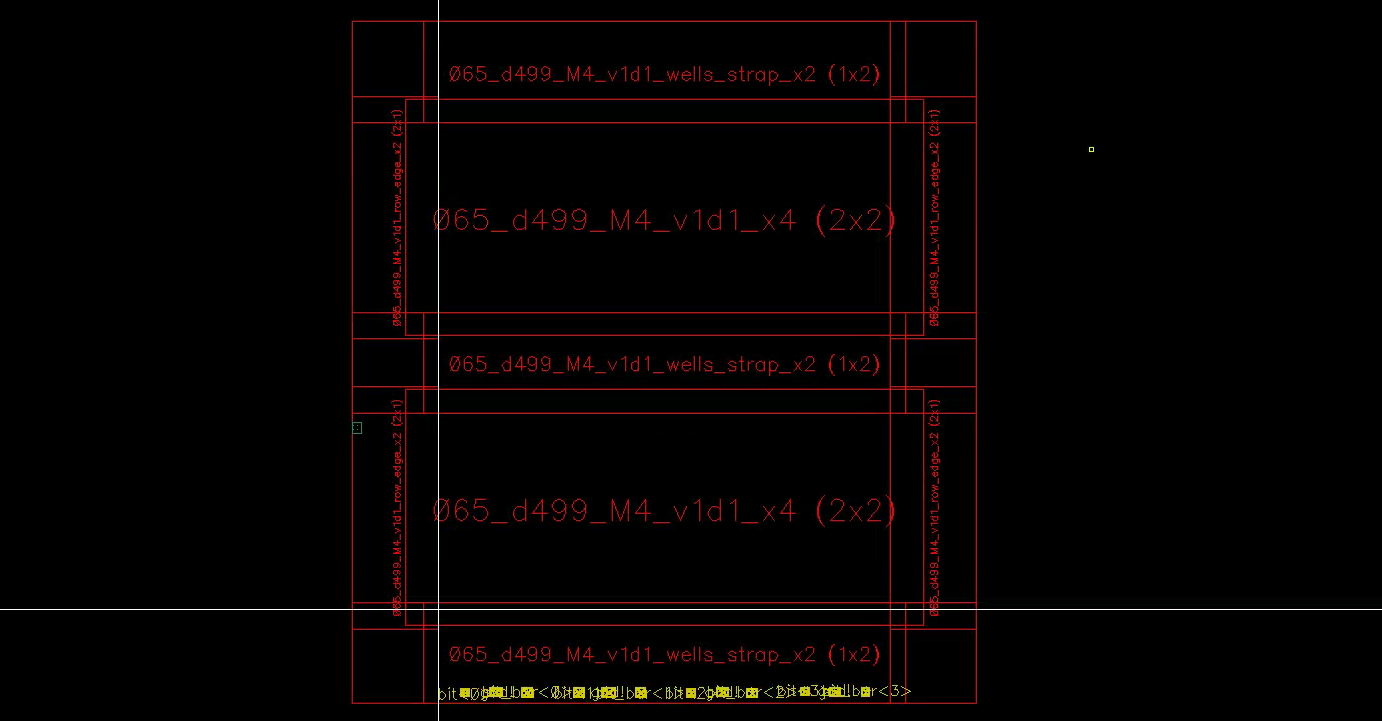

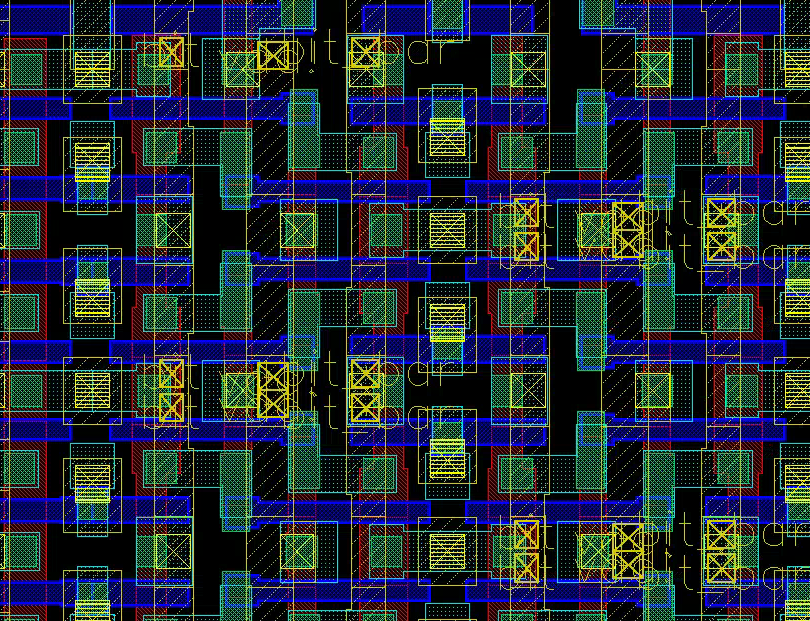

The following demo array was given in Fall 2025.

Take a moment to appreciate this fabulous SRAM.

v1d1_demo_array_4x4 (8x4) contains: (the 065_d499_M4_ prefixes are abbreviated for clarity)

v1d1_x4 (2x2)(4x4)v1d1_x1

v1d1_wells_strap_x2 (1x2)(1x4)v1d1_wells_strap_x1(power strap)

v1d1_row_edge_x2 (2x1)(4x1) (I think they are decap)v1d1_row_edge_x1(x4)

v1d1_corner_edge_x1- M2 and M4 pins

- There is an extra M3 layer at the left that will cause DRC errors. Delete it.

Inner Cells

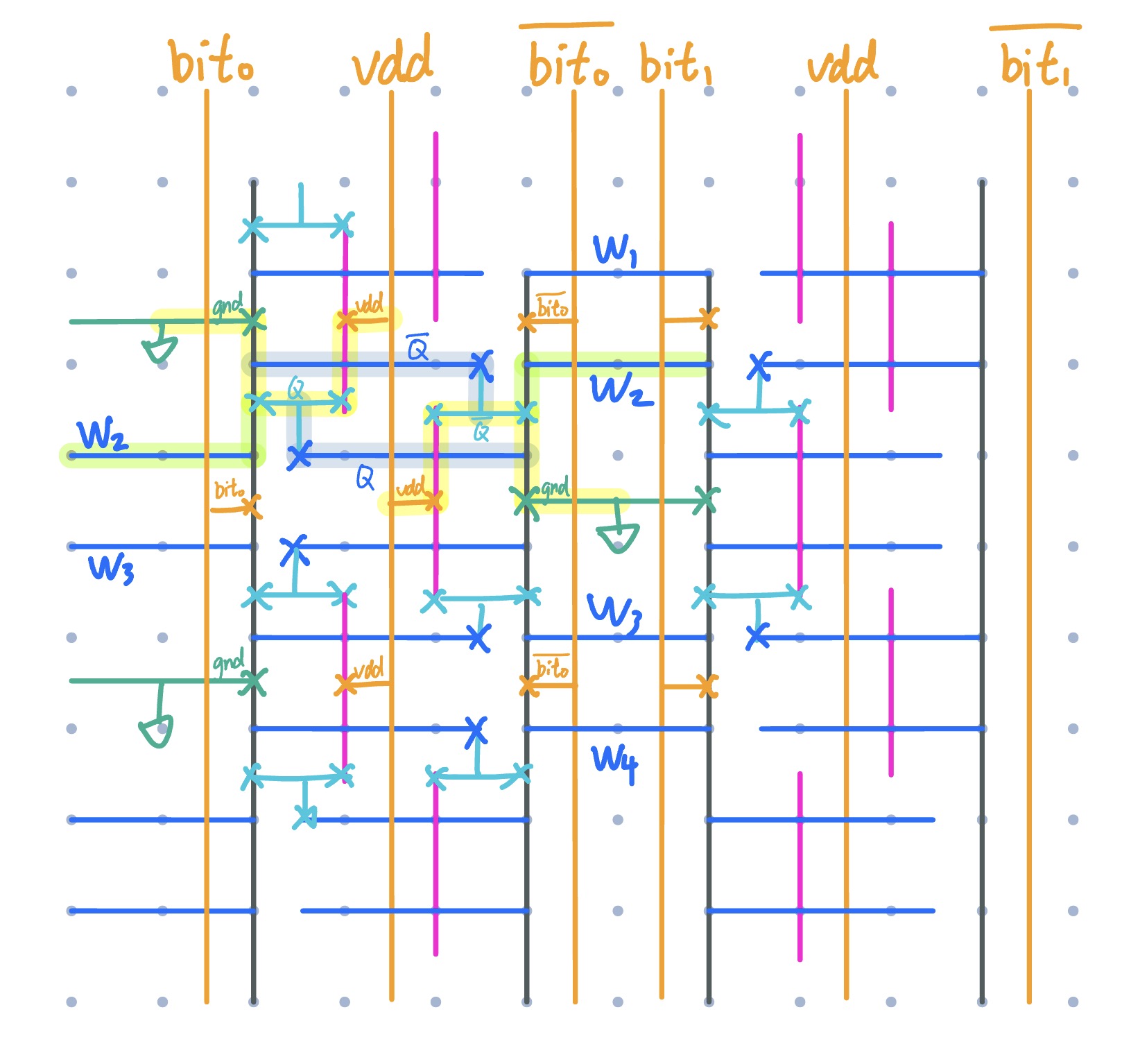

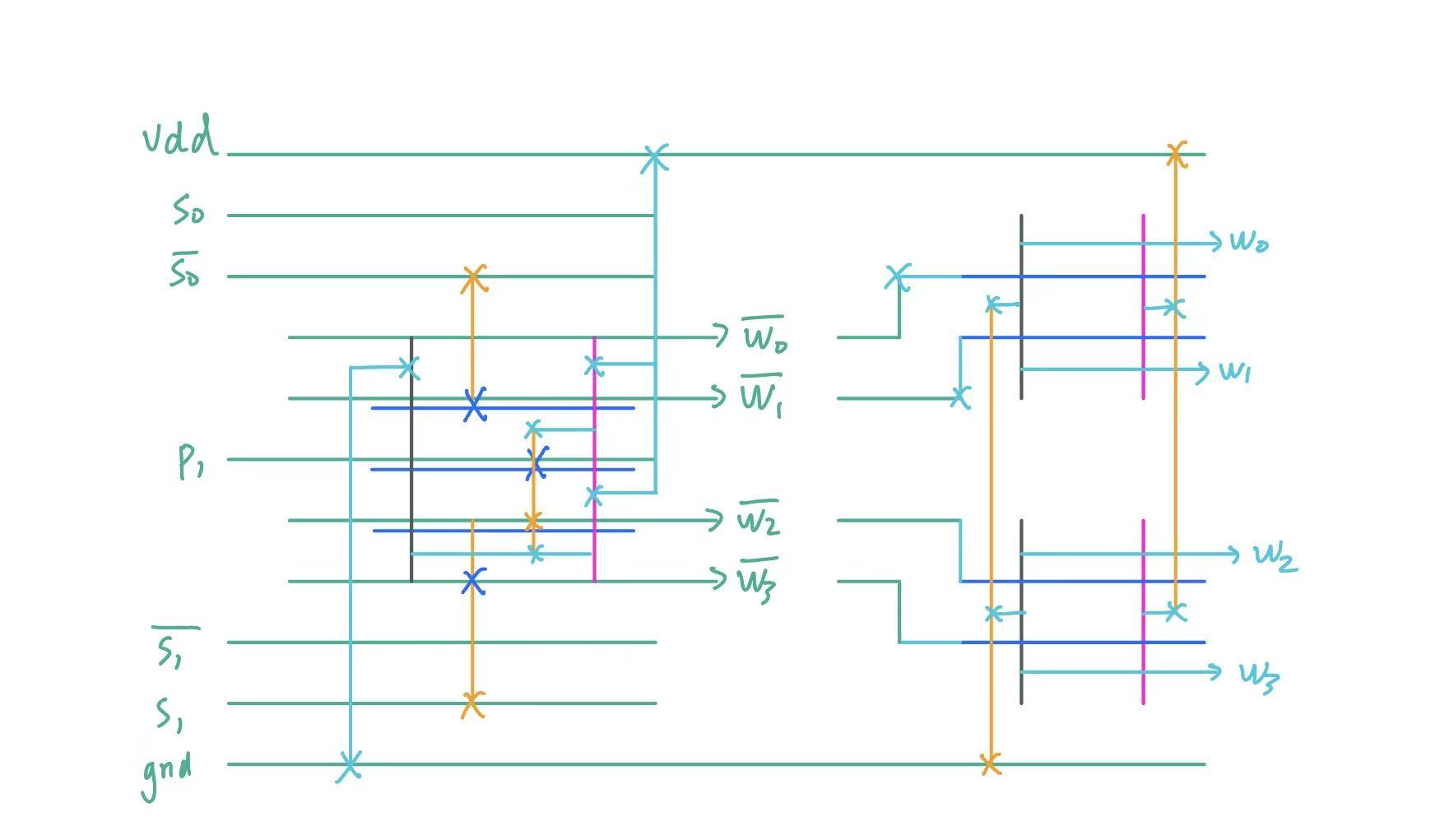

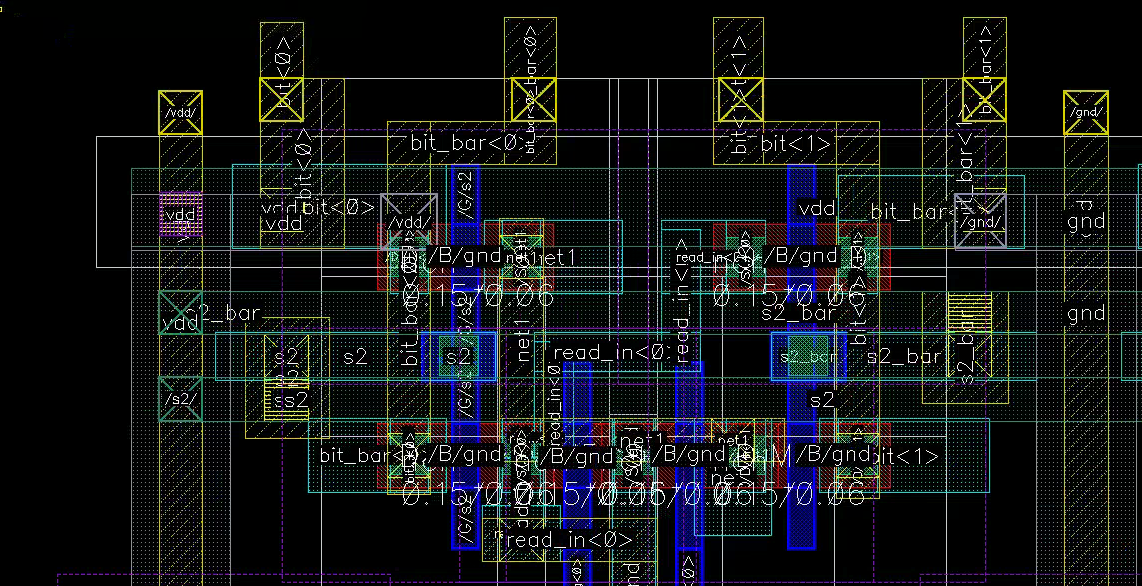

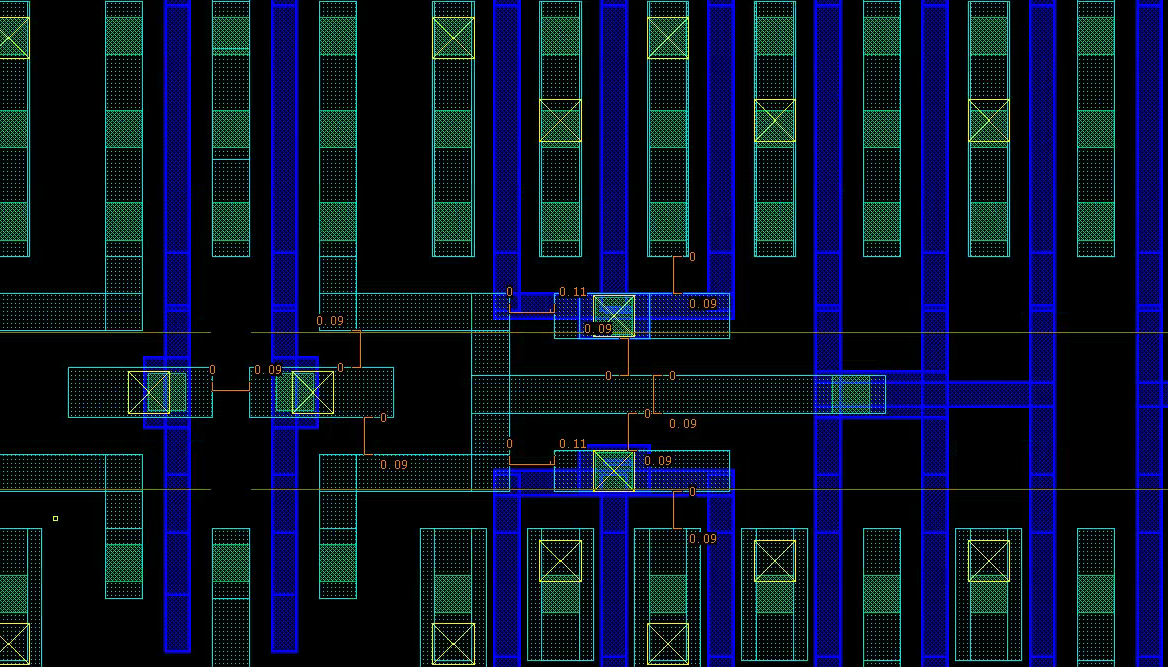

Here is an SRAM section zoomed in. Try to hide the NW and M4 layers, analyze layer by layer, and appreciate such a fantastic design

Below is its intensely annotated stick diagram. I highlighted the cell at wordline<2>, bit<0>, clearly showing the coupled inverters and access transistors.

Meanwhile, appreciate its elegance, and try to make your own layout just as cute

Don’t forget to check DRC and LVS of the SRAM cell. If there are nontrivial errors, tell Shepard to fix immediately!

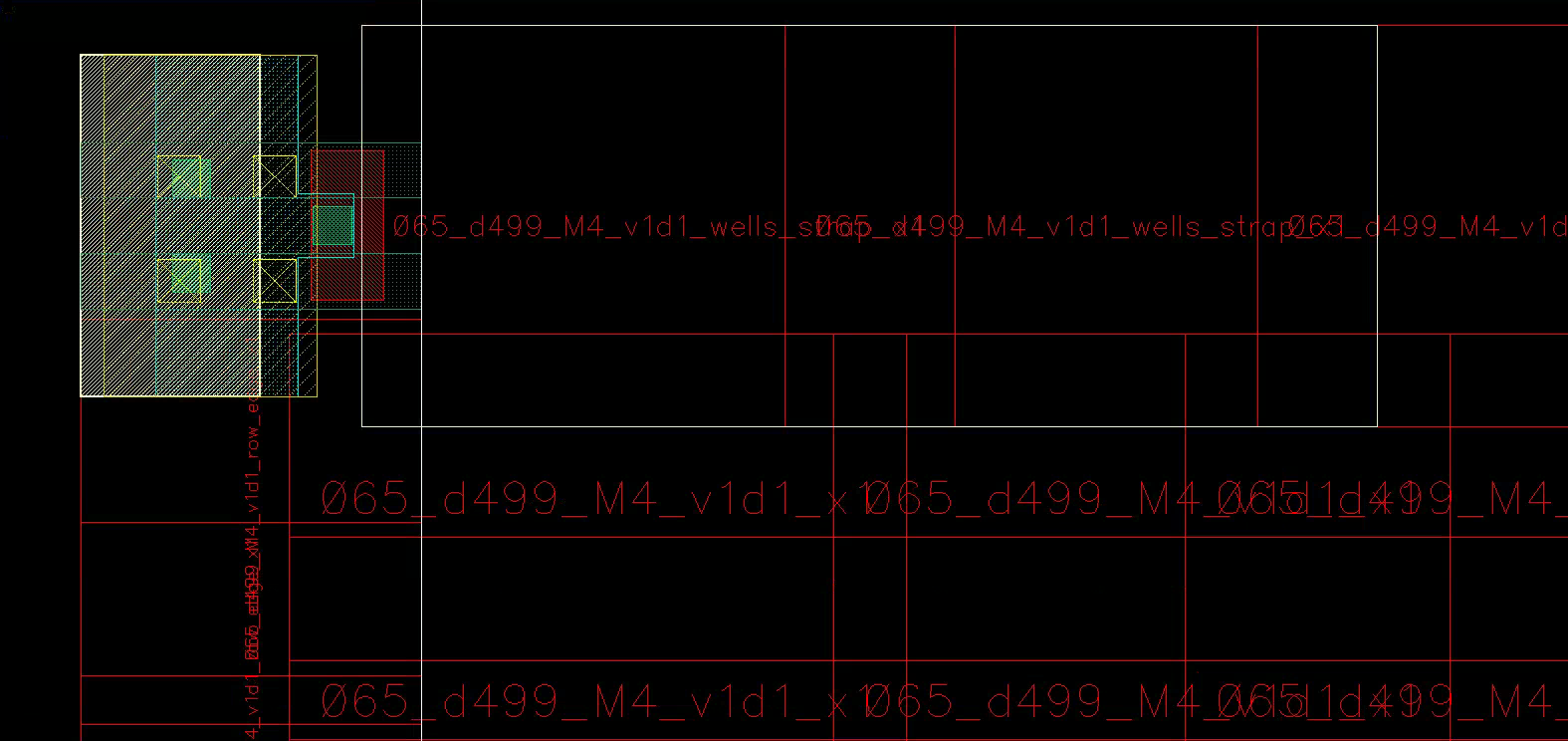

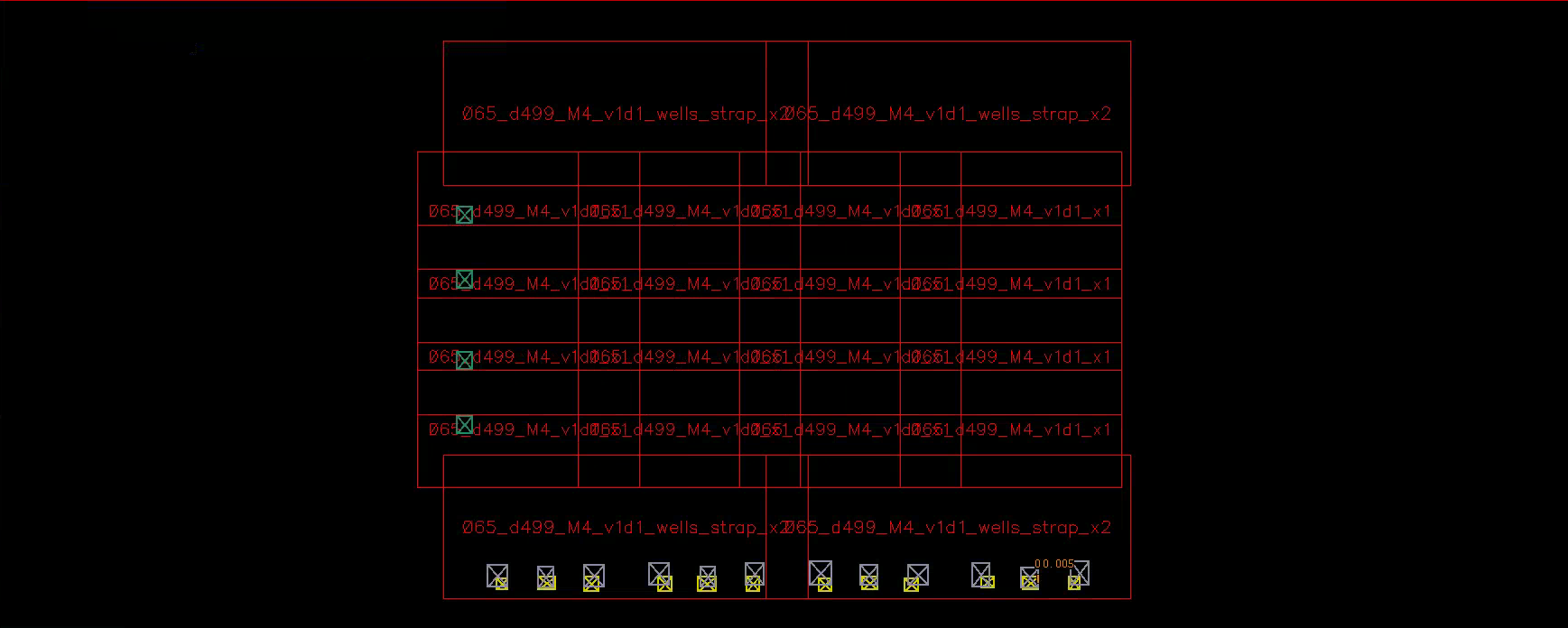

4x16 Layout

Enough appreciation–time to build.

The provided 8×4 array is constructed from 4×4 blocks. Your task is to reorganize this into 4×16. As long as you understand what’s happening, this is very manageable.

You can group 4x4 cells together, and then piece 4 of them for 4x16.

- Make a 4x4 schematic and symbol with four

v1d1_x1symbols- 4 wordlines, bitline

<3:0>

- 4 wordlines, bitline

- Generate a 4x4 layout.

- Move entire rows/columns to save effort

- Make sure they are perfectly aligned. I’d like to look at the vias, as their sizes are fixed

- Sanity check, does your 4x4 dimension match with the sample 4x4 layout?

- Add instances of the top and bottom

wells_strap_x2to the layout. They don’t appear in the schematic, but that’s OK.

- Create a 4x16 schematic and symbol with four of your 4x4

- Generate a 4x16 layout

- Add

row_edgeandcorner_edgeinstances to the layout - Again, make sure everything’s perfectly aligned

- Add

- Check DRC and LVS

- Add the pins.

- The width of the M2 wires vary, but there is a pretty clear “center line”

- Measure the distance between the center lines of

bit<0>andbit<2>. You should get 2.1 um. This is the bit pitch I’ve been talking about - Measure the M2 wires to the left of

bit<0>and to the right ofbit_bar<15>(GND). You should get 16.8 um. If not, something is misaligned. - Add M2 pins for power and bitlines. They don’t have to be perfectly square.

- Add M3 pins for wordlines and power

- Add M4 pins for power

- You don’t have to be perfect for now. We will refine later

Decoder

Shepard has probably showed off multiple decoder designs in lecture and practice exams. However, most people converted to a static CMOS decoder for this project

- With column MUXing, only two rows need decoding.

- Wordlines must be qualified with

phi_1.- Address change happens when

phi_2is high - Evaluation happens when

phi_1is high. - Multiple (even transiently) active wordlines will lead to catastrophic data corruption, as cells will be shorted.

- Address change happens when

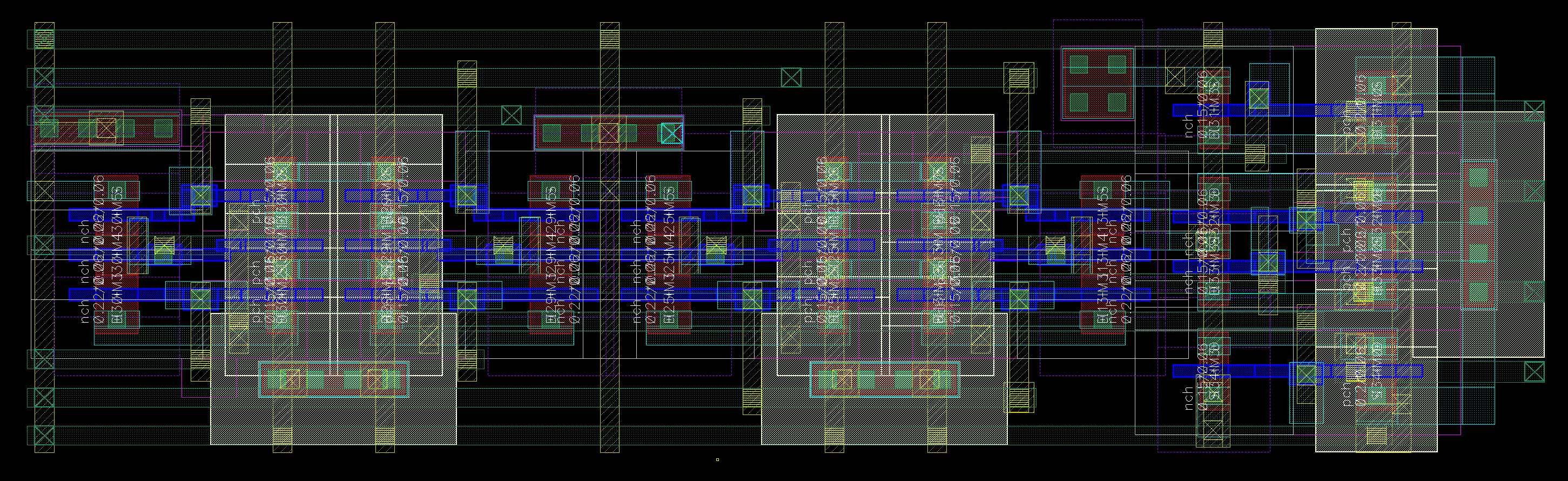

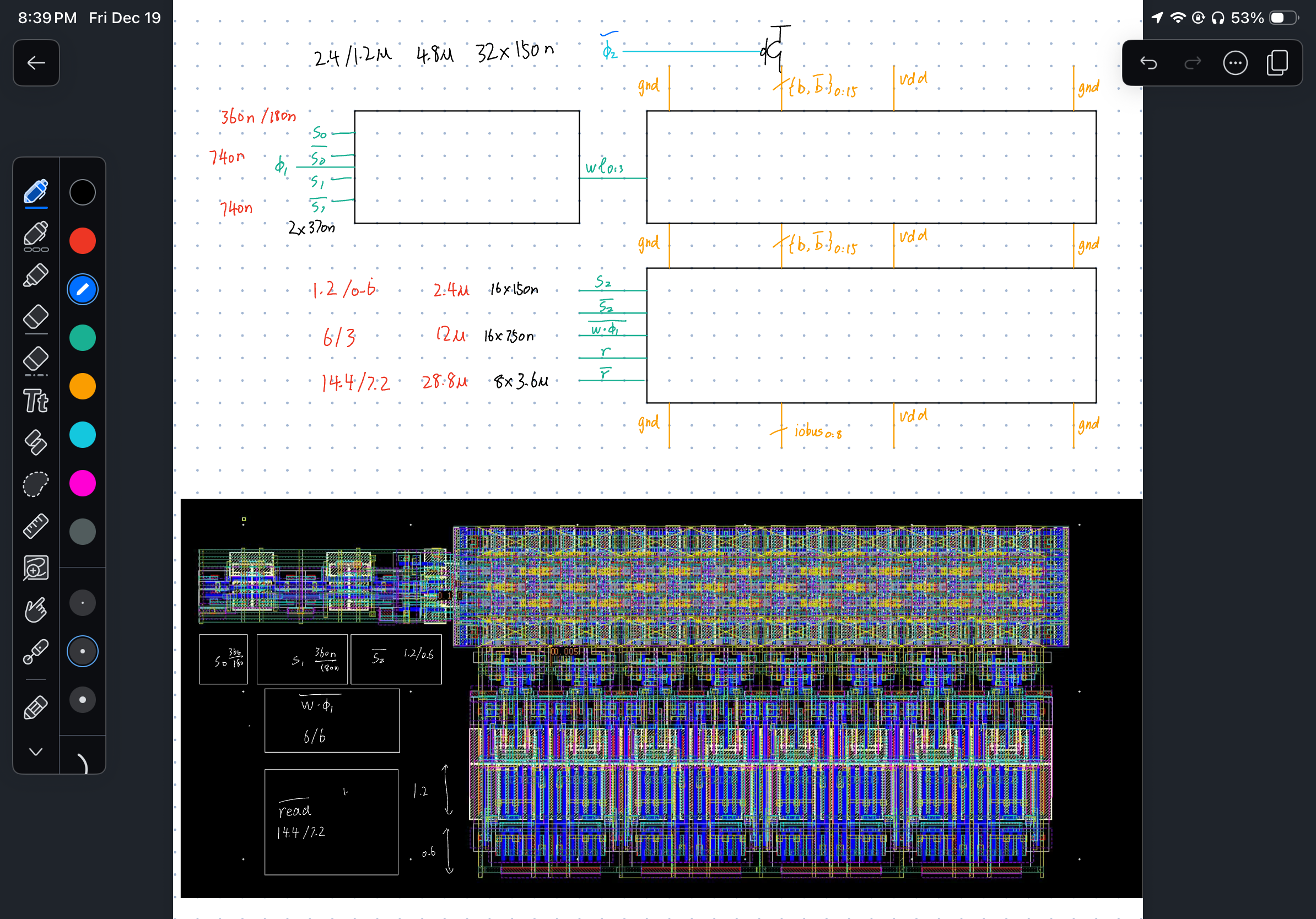

We chose a 4-in-1 NAND-NOT layout that fits neatly within four SRAM rows and scales naturally with predecoding.

The drawback? Kind of huge in width. It will be better for this project if we can put them to a more squared shape.

The idea is simple:

- Spam M3 horizontal wires for all signals and power (Yes they fit)

- Use M2 to fetch the signals vertically from M3

- Use our M2-VIA2-M1-CO-PO stack to control the gates

- Route the outputs with M1-VIA1-M2-VIA2-M3

Implementing it is tricky, but once you have one block, the rest is simple.

Read Write

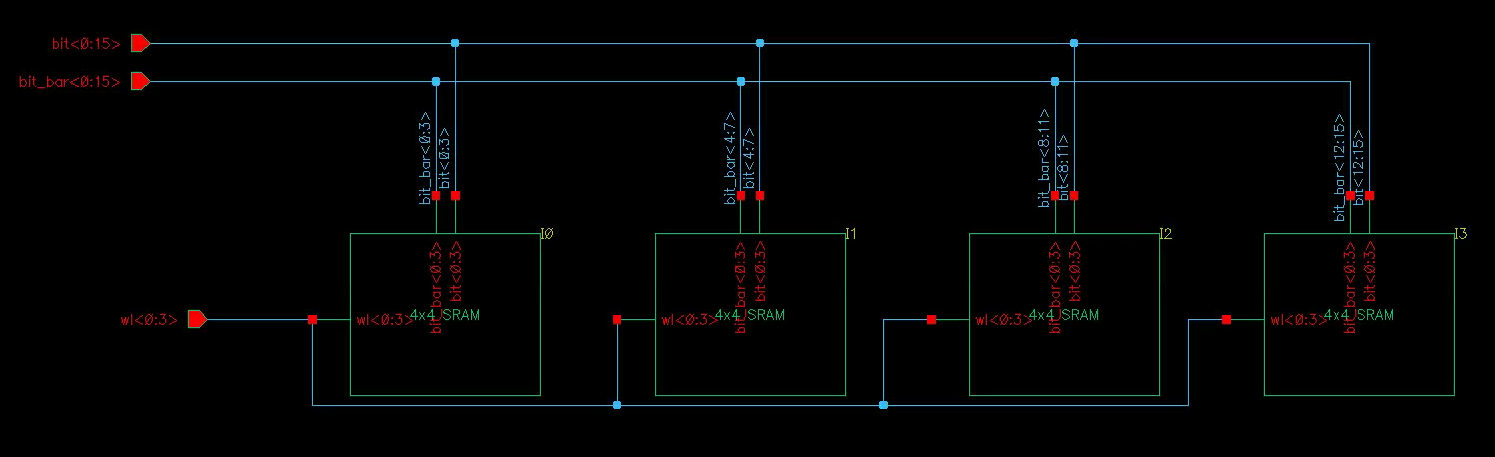

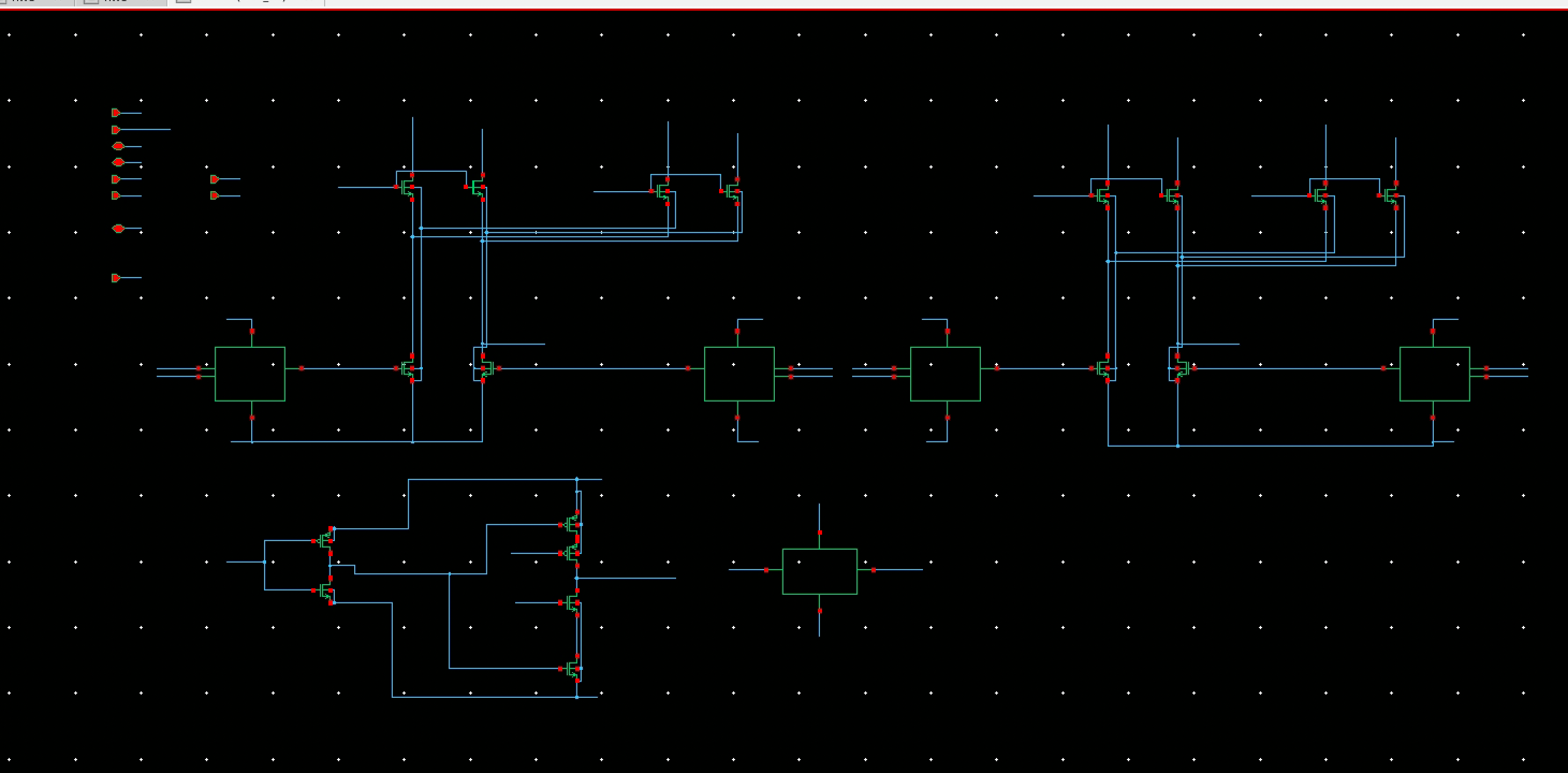

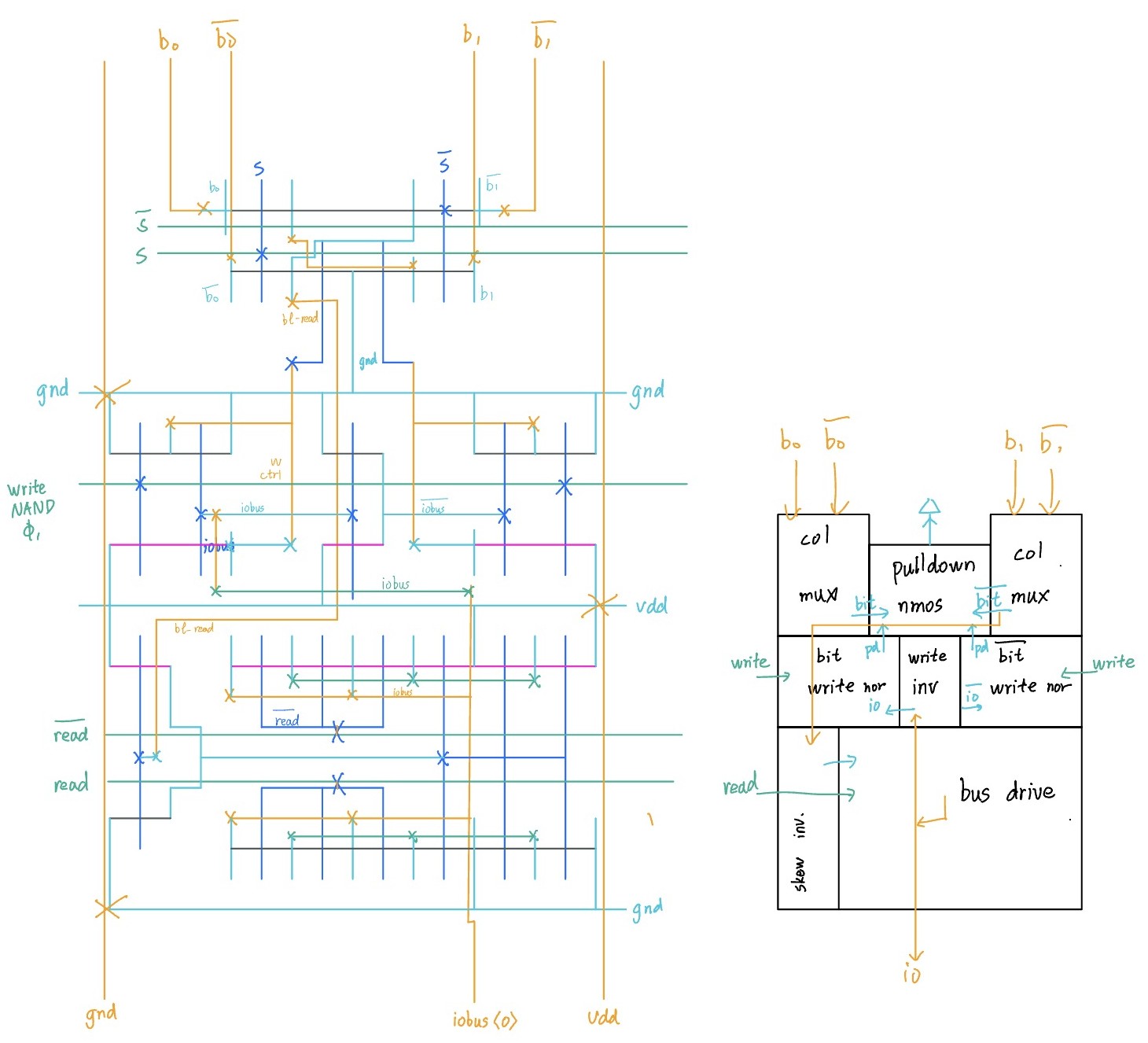

Below is the 2-bit (4 bitline pairs) R/W schematic, closely following lecture

- Column MUX selects between adjacent columns.

- Write Select pulls down the bitliens.

- We merged the

writeanddataNMOSes to save a stack height

- We merged the

- Read Driver taps from

bit_bar, amplifies with a skewed inverter and a bus driver

Testing

Make sure the pre-extraction simulation works very consistently before starting layout, so you can isolate errors as early as possible.

At the schematic level, I’ve summarized a few common failure modes based on my own experience and that of my classmates.

- Forgot to power

vdd!/VDD!/VDD.- If node voltage hover near 0V, or 0.5V, it’s very likely a power issue

- The SRAM cell implicitly uses

vdd!, and after extraction, it may appear asVDD!. - At schematic level, there is a simple way:

- Use 1V

vdcto drivevdd!relative tognd!. - Use 1V

vdcto tie all other powers andgnd! - Use 0V

vdcto tie all other grounds andgnd!

- Use 1V

- Wordline glitch

- Addresses much change only when

phi_2is high. - Probe all wordlines to ensure they are one-hot.

- Addresses much change only when

- Off-by-one inversion

- The lecture circuit is inverted

- Simple test: invert your input vector

- Clock phase overlap

- The circuit should work fine if

phi_1andphi_2are both 50% duty cycle. - If problems appear, try:

- Slow down the clock period

- Reduce the duty cycle for

phi_1andphi_2

- The circuit should work fine if

- Readability and writability

- These are mostly handled in the SRAM cell.

- Make sure the transistors on the bitline add minimal parasitics.

- Close-to-minimum sizings are fine.

- Probe

bitandbit_barto see if it’s a skew issue

- Tristate issues

- Only one driver should be connected to

iobus - When writing,

iobusis driven by testbench sources. The read driver are set in tristate. - When reading,

iobusis driven by the read driver. Use transmission gates in the testbench to disconnect the testbench sources!

- Only one driver should be connected to

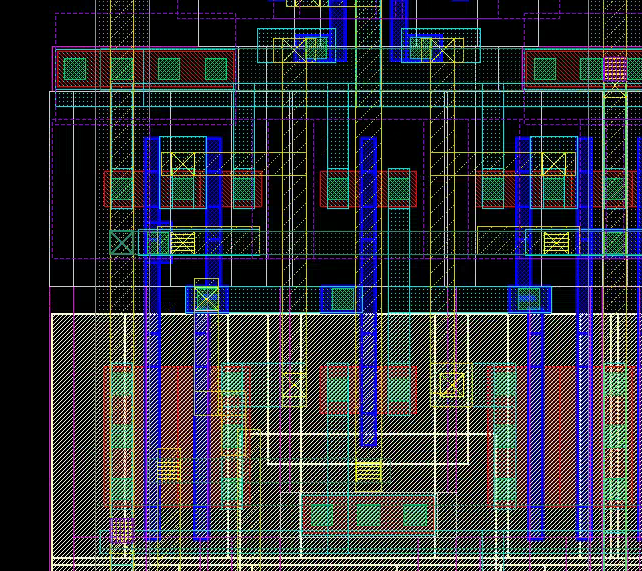

Stick Diagram

This is legacy layout. Horizontal gates may save a lot more space

We used a vertical Poly layout for this part. You will see the pros and cons in a moment. We laid out two units at a time.

Column MUX

Four NMOS devices steer either column into the R/W circuitry.

We initially attempted a single-row diffusion-shared layout and missed by a fraction of um :( The final solution uses gate sharing instead.

A lot of wires, but also a lot of space

The pulldown path is short. Good for delay.

Write Pulldown

Now to the interesting (and hard) part. In lecture, we know that we can control the write pulldown NMOS of bit by write AND iobus (iobus_bar for bit_bar). For stability, we also want to qualify this with phi_1. The logic is:

write AND iobus<i> AND phi_1

iobus<i> will differ from bits, but write AND phi_1 is the same. We factor out the shared term and supply it from outside, drastically reducing the complexity inside!

And bubble push:

(write NAND phi_1) NOR iobus<i>

Omg this is too beautiful

We need iobus_bar<i> for bit_bar<i>. Fortunately, there’s ample space to squeeze in an inverter

Vertical Poly allows aggressive diffusion sharing if S/D Contact and Metal is aligned directly under the M2 bit grid. Otherwise, space is wasted quickly.

Read Driver

The read driver’s pretty straightforward.

- A skewed inverter to handle bitlines

- A large tristate driver for

iobus

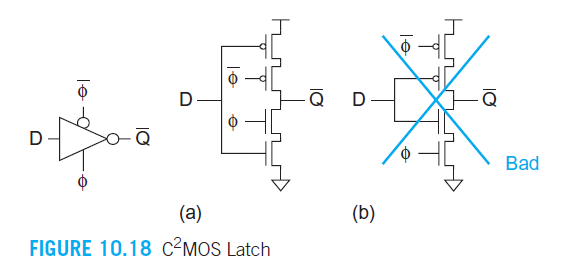

We chose a 4:1 width ratio. You should test it to make sure it works at schematic level.

We then used a (600/300)x3 C²MOS tristate bus driver. Note that it has a stack height of 2. It is discussed in textbook pp 393

Do not add inverters after a tristate driver. That defeats the point.

With careful tuning and diffusion sharing, you can make everything perfectly fit

What if things don’t fit?

Cry, but not too much. You still have to face it

- Check the basics. Start with diffusion sharing, efficient routing/viaing, avoid oversizing, etc.

- Resize device. People constantly miss that. Ask you self: Is the device on the critical path? How slow would it be if I size it smaller? Can I finger it differently? Can I orient it differently?

- Use straight lines. Bends increase contention not only itself, but its neighbors as well! Try to make lines as straight as possible, or shift them away from tight regions.

- Detour. If you’ve really tried, take a detour. Find gaps on each layer, and consider moving your routing to these gaps to free space for the tight area.

- (Temporarily) move to a higher Metal layer. Only do this for short, local routing, as it may horribly interfere with your global routing plans. Also vias are not cheap.

- Accept tradeoffs. If there are truly no ways, increase spacing. Note that this is not an excuse to sloppy layouts. In our case spacing should always be increased vertically (the horizontal dimension fixed at 2.1 um).

A slightly area-inefficient design is not a failure — It’s a deliberate tradeoff. In fact, you can often reclaim the space by fitting in power straps, inverters, or decaps.

An example of diffusion sharing and detour

An example of diffusion sharing and detour

CONGRATS ON FINISHING HALF THE DESIGN PROJECT!!!

Peripheral-Peripheral

The rest of the circuit is what I call the “peripheral” of peripheral circuits, which include:

- PMOS for cell precharge

- Logic for

(write NAND phi_1) - A couple of inverted control signals

- Power grids and pins

This is where overall layout organization starts to hurt. The main challenges are:

- Decide transistor size to drive the shared control signals

- Calculate the total fanout

- I typically make it under FO4, which is fine in practice

- I chose area over delay, not accurately optimizing large-fanout drivers.

- Find a place to place such transistors

- Find a place to prettily place such transistors

- Floorplan the grids that integrate well with the rest of the design

**Here’s how I did it: **

- Draw the core transistors within the grid. Pass DRC. (proof of concept)

- Roughly connect the remaining structures (even if not DRC clean) to pass LVS (proof of concept)

- Go back and refine the details. Resolve the remaining DRC issues.

- STOP for now. Don’t try to make it perfect, as you will probably revisit it

Disclaimer: these sizings are for an older version. Calculate your own!

With these decisions in-place, you can lay out the whole thing:

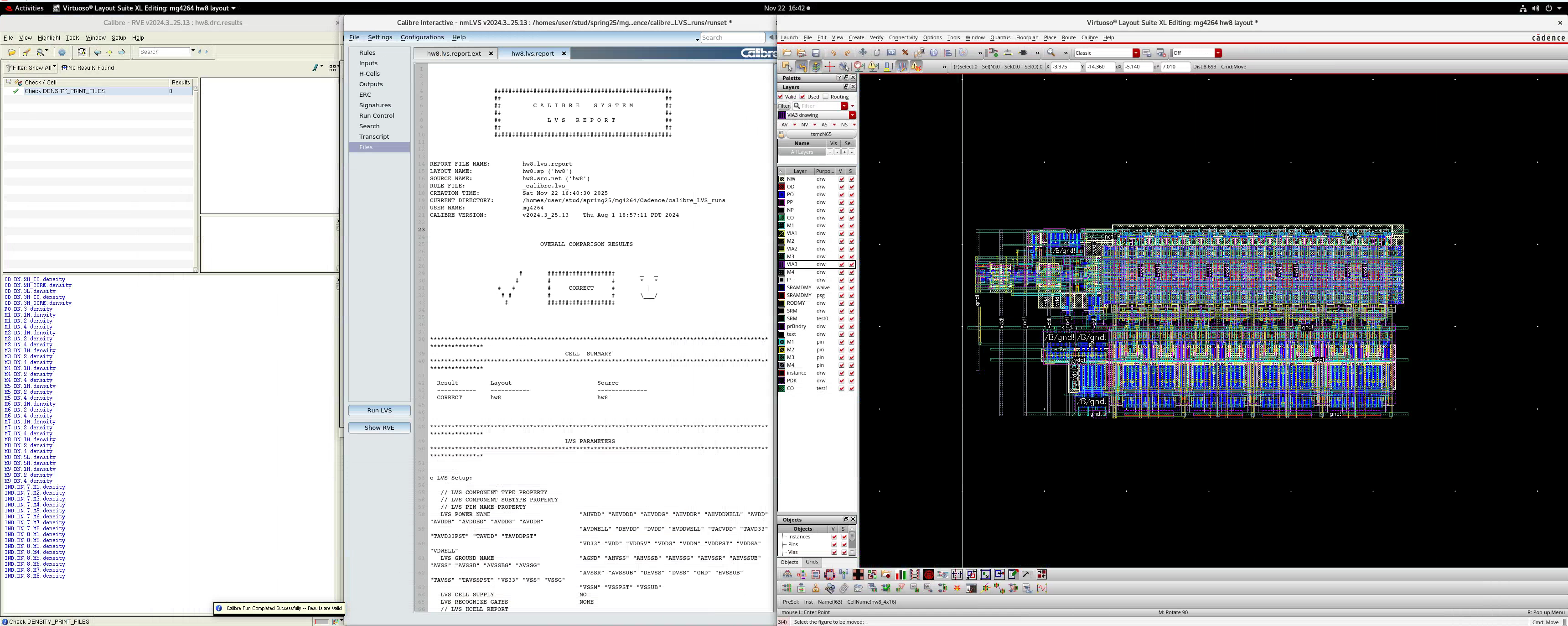

Calibre

It’s a pain dealing with third-party libraries

LVS

You may get a few LVS warnings on M2 pin short. This is from the v1d1_x1 cells’ M2 pin label. The M4 pins are fine.

- We externally connected power through M4 and M2 at the boundary

- As long as you leave the “shorted” pins in the center untouched, it should work fine

PEX

You might get the following warnings from extraction:

WARNING: [FDI3034] Schematic instance XI24/XI63/XI3/XI0<0>/M0 not found, use found instance XI24/XI63/XI3/XI0<0> instead.

WARNING: [FDI3046] Failed to create mapping for device "nchpg_sr". Netlist for "XI24/XI63/XI3/XI0<0>/M0" instance has more pins than schematic view.

WARNING: [FDI3014] Could not find cell mapping for device nchpg_sr. Ignoring instance XI24/XI63/XI3/XI0<0>/M0.

Those are fine, since the internal schematic for the 6T SRAM cell is not given. The entire instance will be used for the extraction.

- If post-extraction simulation doesn’t work, try a more tolerant testbench timing here

They post-extraction delays are around 50 ns.