Demystifying Cache—From Bytes to Tags

Published:

Demystifying Cache: From Bytes to Memory

Fundies TA Team

Updated November 2025

Breaking down cache address bits is tricky. In this guide, we’ll step through in detail how to partition a 32-bit address and work through some problems to test your understanding :)

Contents

There are multiple ways to explain this. Below I’ll assemble those pieces step by step. If you’re already comfortable with the address breakdown, feel free to skip ahead to the practice problems to test your knowledge!

- Cache and Address Space

- Cache Address Breakdown

- Byte Offset: bytes in a word

- Block Offset: words in a block

- Set Index: blocks in a way

- Mapping Cache to Memory

- Ways & Associativity

- Practice: Dividing Address Bits

- Challenge Problem

Cache and Address Space

Be careful with units! They may appear as bit (b), byte (B), or word (4B)!

- Our MIPS memory uses 32-bit addresses (0x00000000 through 0xFFFFFFFF in HEX). Each byte in memory has its unique 32‑bit address.

- A word in MIPS is 4 bytes (32 bits). We address by byte, but loads/stores move the entire word.

Cache Structure

The circuit implementations can be found in the lecture slides and Harris & Harris section 8.3.2: “How Is Data Found” (pp 482-488)

A cache is organized as:

Cache

└── Ways (if associative)

└── Blocks

└── Words

└── Bytes

Let’s create a cache bottom-up:

Don’t confuse this nested structure with the “hierarchy” of L1/L2/L3 caches

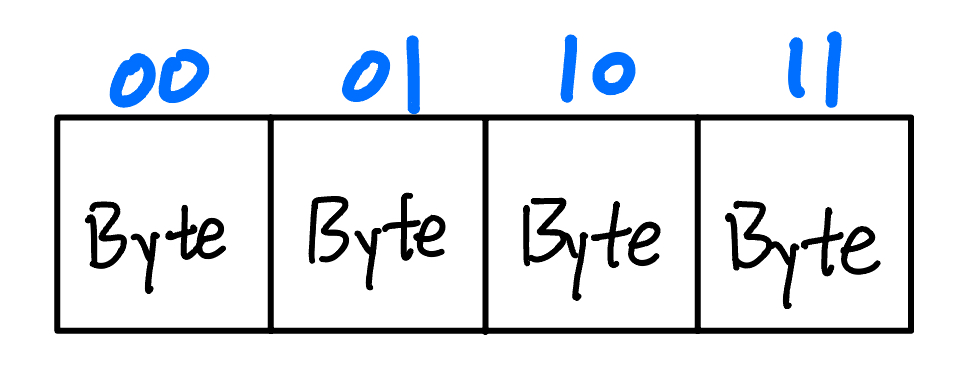

Byte Offset

The byte offset selects bytes within a 4-byte word.

- It takes \(\log_2(4) = 2\) bits to represent the 4-byte addresses: 00, 01, 10, 11

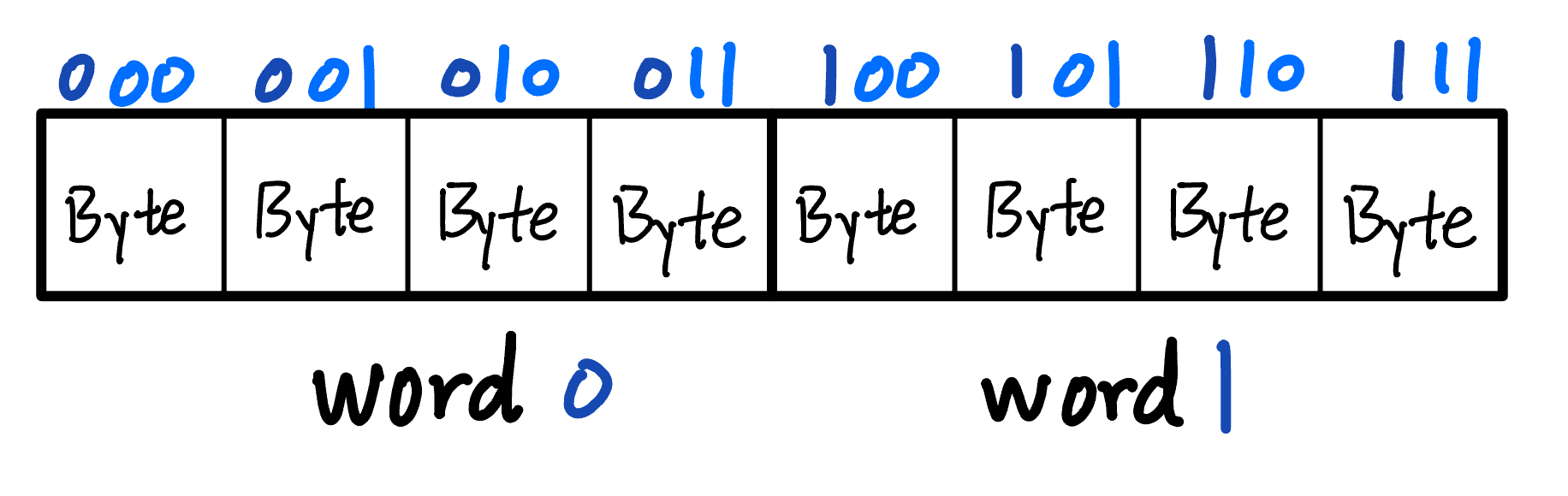

Block Offset

Caches read/write in blocks, which may contain multiple words. To locate bytes within a block, we break the low-order address bits into two parts.

Let’s make the block 8 bytes, holding 2 words. We need \(\log_2(8) = 3\) bits of index. They are split into:

- Block offset (which word in the block, navy): \(log_2\frac{\mathrm{block\,size}}{\mathrm{word\,size}} = log_2\frac{8B}{4B} = 1 \mathrm{bit}\)

- Byte offset (which byte in the word, blue): \(log_2\frac{\mathrm{word\, size}}{\mathrm{byte\, size}} = log_2\frac{4B}{2B} = 2 \mathrm{bits}\)

- Since transfers are word-aligned, those two bits are always 00

Some texts combine the block-offset and byte-offset bits into a single “offset” field.

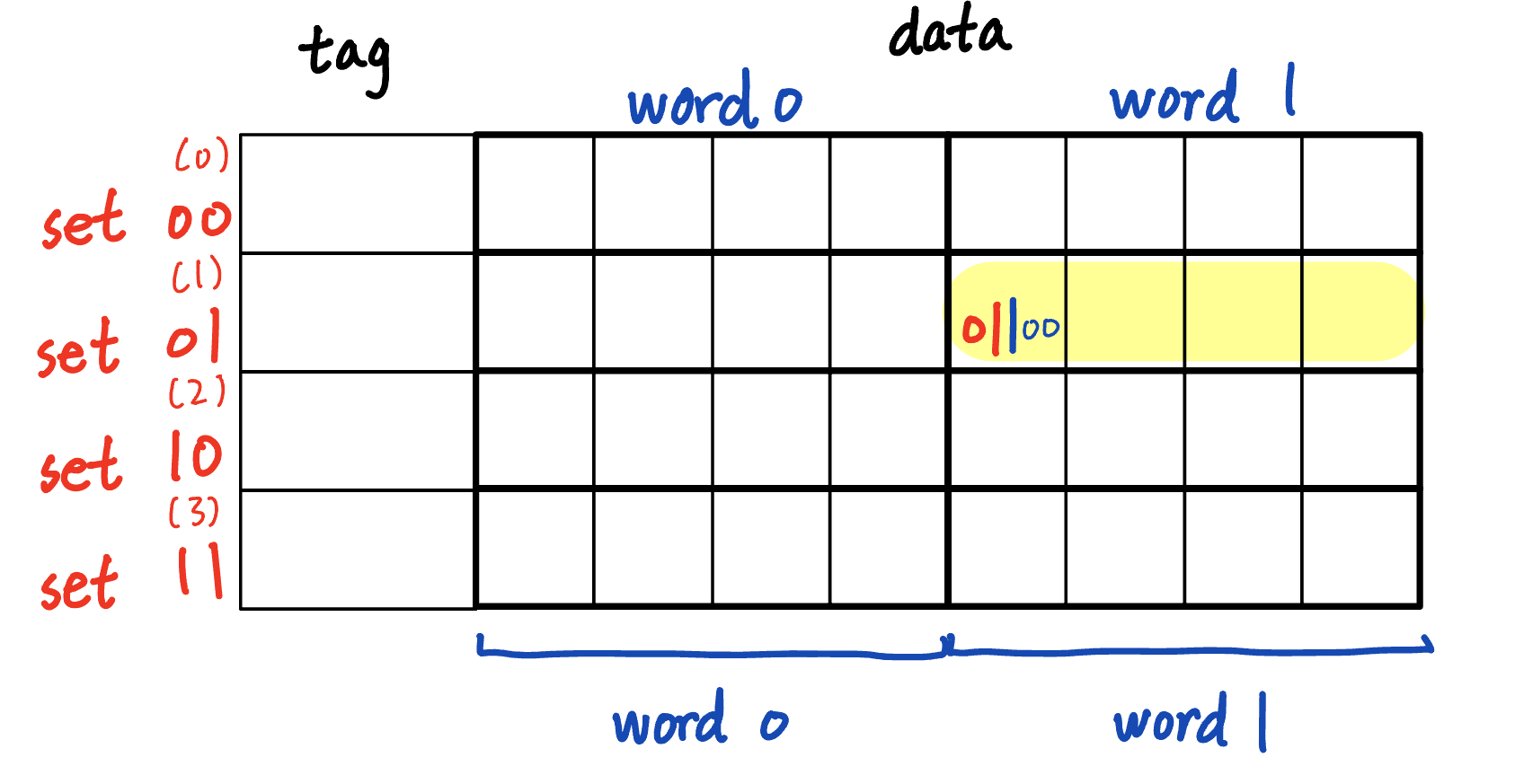

Set index

In a cache way, each block lives in exactly one “set.” If each cache way has W bytes and each block is B bytes, then we have

- Number of blocks \(= \frac{W}{B}\)

- Set index bits \(= log_2\frac{W}{B}\) Let’s make each way contain 4 total blocks (8 words, 32 bytes). The address range is 00000 - 11111. The set index will be the two leading bits.

For instance, the highlighted word has address 01 1 00 in the cache, where

- 01 (2 bits, red): set index

- 1 (1 bit, navy): block offset

- 00 (2 bits, blue): byte offset

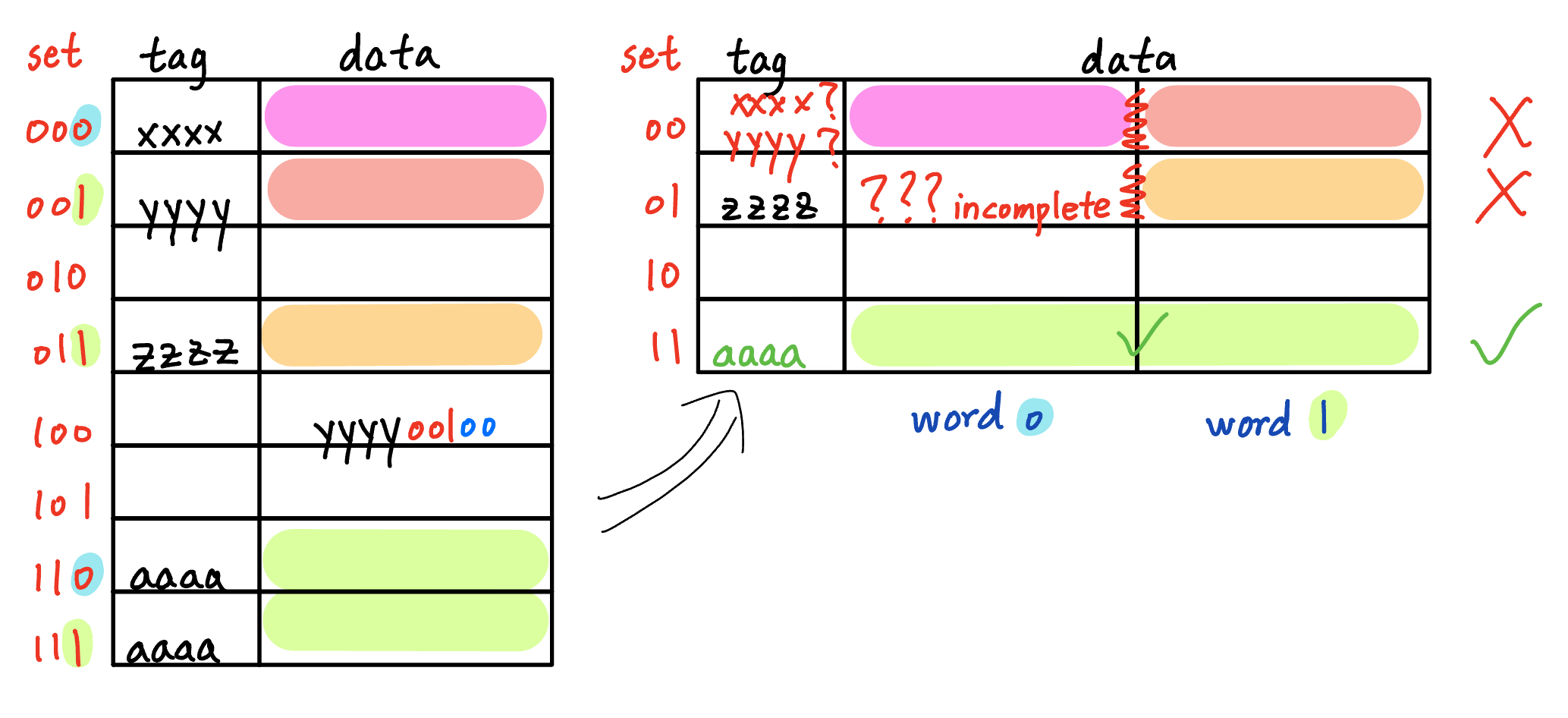

Mapping One-way Cache to Memory

Main memory is huge (32-bit addresses), but caches are small (ours has a 5-bit address space). A cache acts like a small set of “drawers” that hold recent data. To cache a memory address:

- Take the lower 5 bits (set index, block offset, byte offset) to map to its set (drawer)

- The remaining 27 bits form the tag, identifying which region of main memory is stored in that drawer.

When looking up a cache:

- Use the set index bits to pick a set

- Since the entire block is cached (spatial locality), the byte and block offsets won’t matter.

- Compare the stored tag with the addressed tag

- If equal, hit

- If not or empty, miss: load the entire block from memory into the cache and update its tag

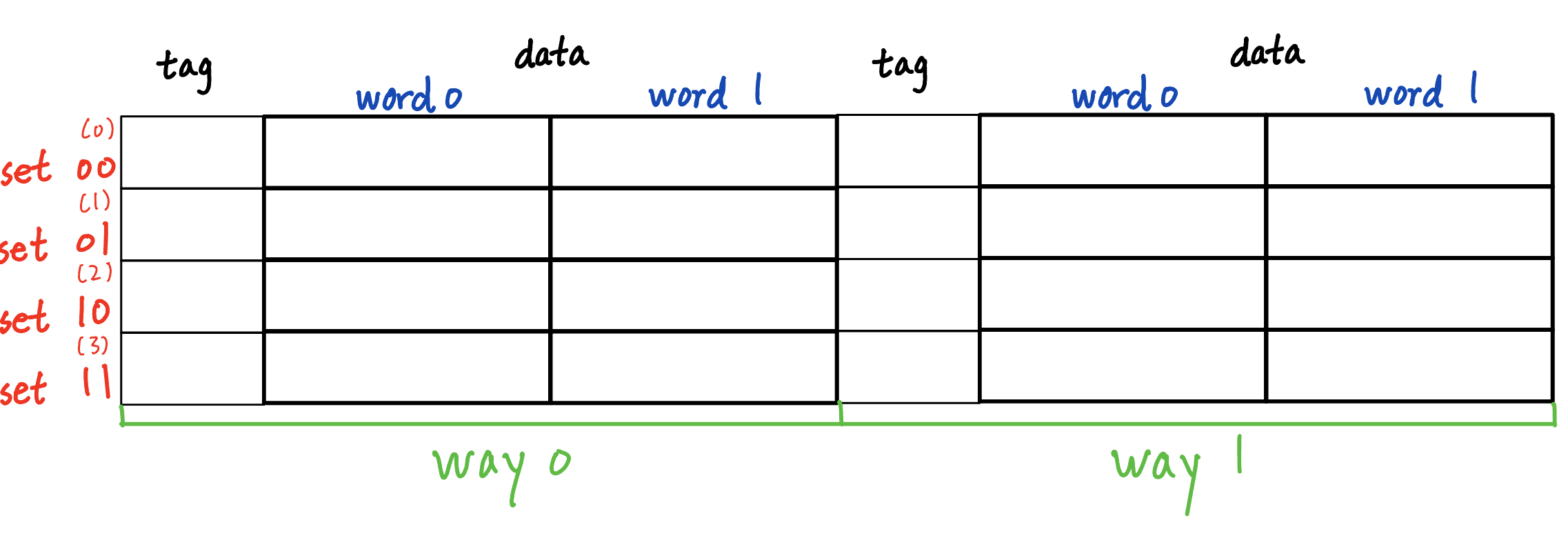

Multi-way Cache and Associativity

In a direct-mapped cache. If a new memory address maps to the same set, it overwrites that entry

To prevent that, we make each set hold k blocks (k-way associative)

- A newly cached block can go into any empty way in that set; overwriting only happens when all k ways are occupied

Making our 32-byte direct-mapped cache into a 2-way set-associative would need 64 bytes

Lookup is similar:

- Set index selects the “drawer” (set).

- Compare incoming tag with all k tags in that set.

- If any matches, hit. A MUX selects the correct block.

- If none match, miss: load the block from memory into one of the k ways and update its tag.

Practice: Dividing Address Bits

Let’s turn this configuration into a Fundies problem and peel the onion backwards!

Given a 64-byte 2-way associative cache with a 64-bit block size, divide the address bits into tags, set index, block offset, and byte offset

- Find the size of each way: 64 bytes / 2 ways = 32 bytes/way

- Find the number of sets (blocks in each way): 32 bytes / (8 byte/block) = 4 sets

- 2 bits of set index (take the log)

- Find the number of words in a block: (8 byte/block) / (4 byte/word) = 2 words/block

- 1 bit of block offset

- Find the number of bytes in a word: always 4 bytes/word

- 2 bits of byte offset

- The rest of the address bits are the tag: 32-2-1-2=27 bits

Tag Set idx Block off Byte off | Total

27 2 1 2 | 32

easy!

Challenge Problem

Here’s a challenge problem taken from last year’s PS, which really tests your understanding of caches and address splitting:

A CPU may change its cache parameters mid-execution For each change, decide if existing cached blocks remain valid or must be discarded.

Hint: sketch the old and new address partitions side-by-side. Write out how many tag, index, and offset bits of each configuration before and after the change.

- Direct-mapped: block size doubles from 1 word / block to 2 words / block

Answer

Invalid: This requires merging two adjacent blocks. You can’t guarantee both halves are present, or that they are mapped from the same tag in memory. Cache is not an injective mapping.

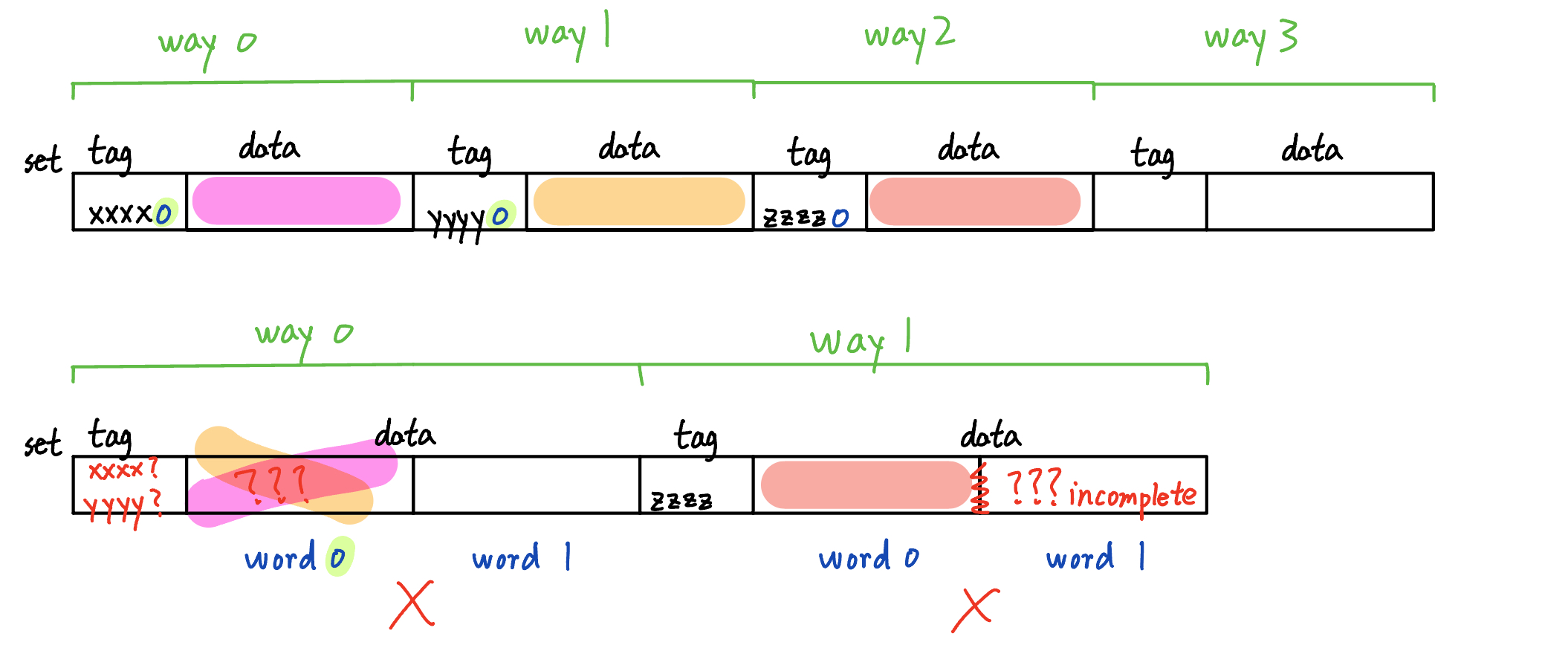

- Direct-mapped: block size halves from 2 words / block to 1 word / block

Answer

Valid: Each smaller block is a contiguous sub‐block of the larger one. Data is already present, and their tag remains the same. One old block‐offset bit (LSB) becomes a set‐index bit. - How would your answers to 1 and 2 change if the cache were fully associative?

Answer

Same logic: merging blocks in different ways may lead to discontinuous or incomplete blocks, but splitting is fine.

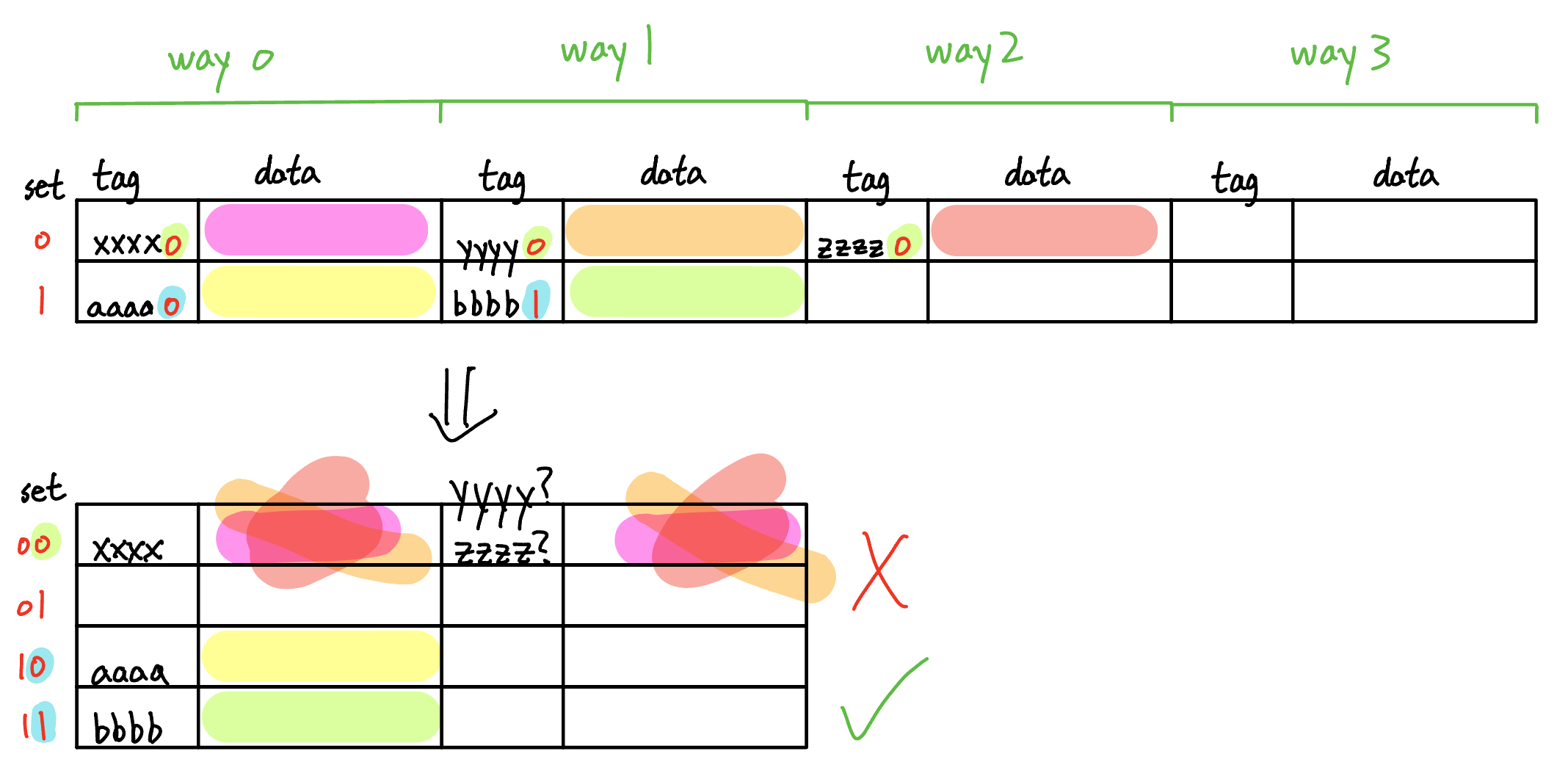

- Set associative, goes from 4-way to 8-way associative

Answer

Valid: Associativity doubles → sets halve → a former set-index MSB becomes a tag bit. Existing placements remain legal, as tag bits can take any value anywhere in the cache. - Set associative, goes from 4-way to 2-way associative

Answer

Invalid: Associativity halves → sets double → a former tag bit becomes a set-index MSB. Blocks with different tag bits but the same tag LSB may collide in the same new set.

- Can you see a pattern?

Answer

Invalid: Increasing block size or reducing associativity both *collapse* the cache's structure: multiple previously distinct blocks now map to the same set. Existing blocks cannot be safely reinterpreted