Understanding Hazards

Published:

Understanding Hazards, Forwarding, and Stall

Fundies TA Team

Updated November 2025

There’s a lot going on in a pipelined processor. Forwarding paths, stalls, bubbles… it adds up fast!

In this article, we review every essential aspect of MIPS pipeline hazards, from identifying hazards, to deriving the logic, to building the circuit, and finally solving a complicated example, so you can see exactly how all the pieces fit together.

Contents

You don’t have to remember “every wire”. But do have a solid sense of all the ideas behind them

- What Is a Hazard

- Producer-Consumer Types

- Types of Forwarding

- M → E (ALU→ ALU)

- W → E (Load → ALU)

- M → D (ALU→ Branch)

- W → D (Load → Branch)

- Implementing the Hazard Unit

- Forwarding Logic

- E Data Path

- D Data Path

- Stalling Logic

lwstallLogicbranchstallLogic- Stalling Circuit

- Forwarding Logic

- Branch Misprediction and Flushing

- Example Execution Trace

What Is a Hazard

In a pipeline, a hazard occurs when a subsequent (consumer) instruction needs a register value that’s not yet available from the producer.

In a 5-stage MIPS pipeline without forwarding, the producer writes its result to the register file (RF) in the Writeback (W) stage, and the consumer reads from the RF in its Decode (D) stage.

ins1 | F | D | E | M ||W |

ins2 | F |×D | E ||M | W |

ins3 | F |×D ||E | M | W |

ins4 | F |↓D | E | M | W |

If ins1 produces a register r1 and later instructions want to use it:

ins2Decodes whenins1is only in E. Value not in RF :(ins3Decodes whenins1is only in M. Value not in RF :(ins4Decodes whenins1is in W. Now the RF has the value :)

RF write happens at the first half-cycle, and RF read happens at the second half

Most MIPS instructions are ALU instructions whose results are produced after the Execution stage. That means we can often bypass the RF entirely and directly forward (↓) the results to the next instruction’s E stage:

ins1 | F | D | E ||M ||W |

ins2 | F | D |↓E ||M | W |

ins3 | F | D |↓E | M | W |

ins4 | F |↓D | E | M | W |

Producer-Consumer Types

Not all instructions rely only on the ALU. Let’s classify the instructions based on when they produce their results and consume their operands.

For this discussion, “ALU” instructions: typical ALU operation that is not a branch or load

If a result is produced at the end of Execute, it will be written into the

Ex-Mempipeline register and will become usable at the start of the next stage (here it’s M) We treat this next cycle as the moment when the result is forwardable

- Producers

- ALU instructions produce their result at the end of the Execution stage (forwardable at M)

- Loads produce their result at the end of the Memory stage (forwardable at W)

- Consumers

- ALU instructions consume their source registers in Execution

- Branches (with early resolution) consume in Decode

Forwarding Types

We’ll say instructions are “one apart” if one directly follows the other in program order.

For each producer-consumer pair, we have a different case. Suppose add, beq, lw have data dependencies

1. M → E (ALU → ALU)

add | F | D | E ||M | W |

add | F | D |↓E | M | W |

M → E forwarding can happen at any sequence

2. W → E (Load → ALU)

lw | F | D | E | M ||W |

xxx | F | D | E ||M | W |

add | F | D |↓E | M | W |

The load result appears only at the end of M (forwardable at W).

Since W and E are two stages apart, W → E forwarding needs at least two instructions apart. If not, the load data is not ready to forward (×):

lw | F | D | E | M |*W |

add | F | D |×E | M | W |

We must stall (*) the consumer for one cycle to forward W → E. This is called lwstall

lw | F | D | E | M ||W |

add | F | D*| D |↓E | M | W |

3. M → D (ALU→ Branch)

Similarly, M → D forwarding needs to be at least two instructions apart.

add | F | D | E ||M | W |

xxx | F | D ||E | M | W |

beq | F |↓D | E | M | W |

Otherwise, we need a branchstall

add | F | D | E | M |*W |

beq | F |×D | E | M | W |

add | F | D | E ||M | W |

beq | F | D*|↓D | E | M | W |

4. W → D (Load → Branch)

This is the worst case. The dependent instructions need to be three apart.

Note that I didn’t draw a forwarding arrow. W → D is a regular RF write/read

lw | F | D | E | M | W |

xxx | F | D | E | M | W |

xxx | F | D | E | M | W |

beq | F | D | E | M | W |

Otherwise, it may require both a lwstall and a branchstall

lw | F | D | E | M |*W |

beq | F |×D | E | M | W |

lw | F | D | E | M | W |

beq | F | D*| D*| D | E | M | W |

Implementing the Hazard Unit

OK, we know what to do. Let’s derive the logic and implement the circuit.

Forwarding Logic Producer values to forward:

- From M:

ALUOutM - From W:

resultW

Consumer to forward to:

- To E

- To D

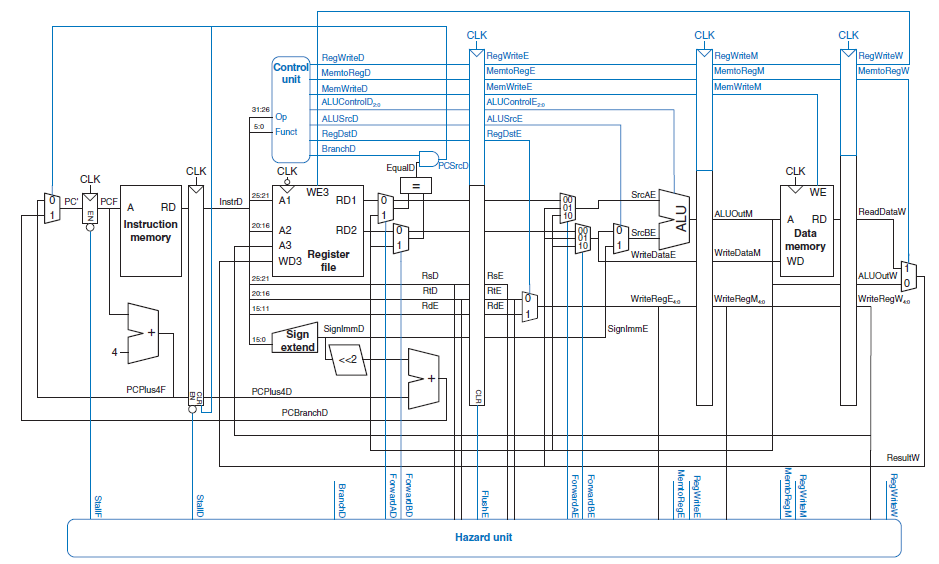

Forwarding E Datapath

- The

Adata path at Execution is controlled by MUX, with select bitsfwdAE:

if ( # 10: M → E

RegWriteM # Instr in M writes to a reg

AND (rsE != 0)

AND (rsE == WriteRegM) # Instr in E reads what M writes

)

feed ALUOutM # 10

else if ( # 01: W → E

RegWriteW # Instr in W writes to a reg (load)

AND (rsE != 0)

AND (rsE == WriteRegW) # Instr in E reads what W writes

)

feed resultW # 01

else # no forwarding

feed RF result # 00

- The

Bdata path is similar. Just replace everyrsEbyrtE

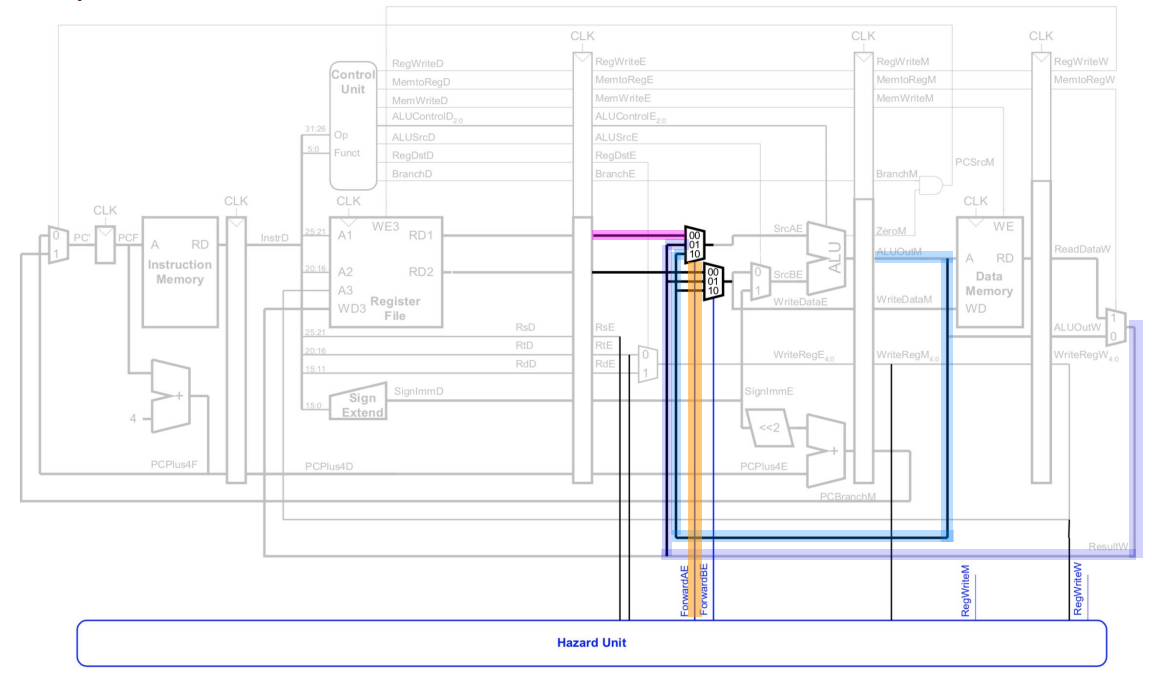

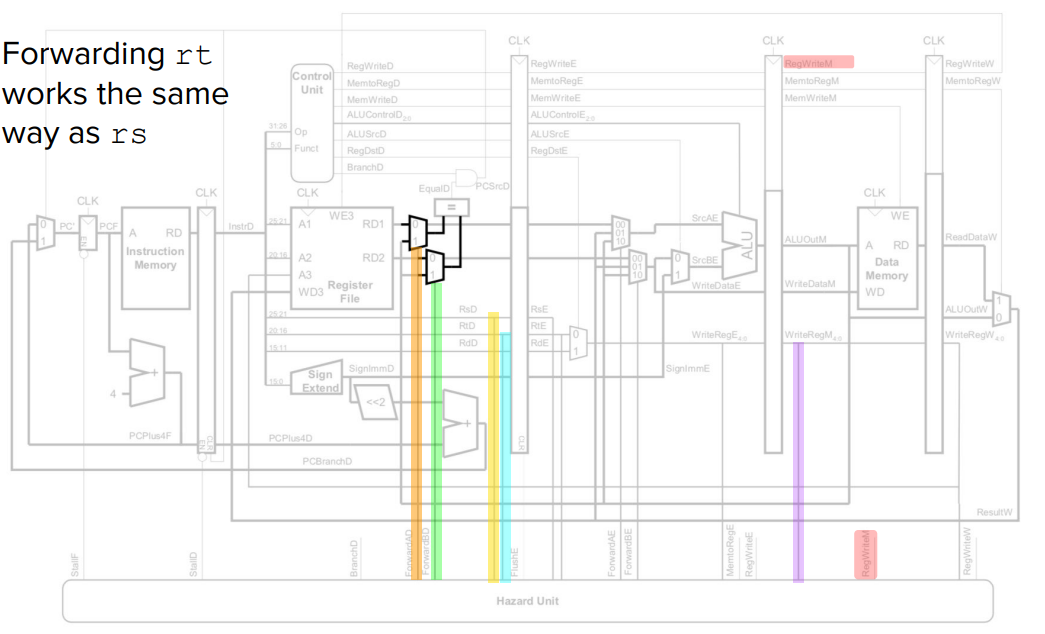

Forwarding D Datapath

- The

Adata path at Decode is controlled by MUXfwdAD

if ( # M → D

RegWriteM # Instr in M writes to a register

AND (rsD != 0)

AND (rsD == WriteRegM) # Instr in D reads what M writes

)

feed ALUOutM # 1

else # no forwarding

feed RF result # 0

- The

Bdata path is similar. Just replace everyrsDbyrtD

Stalling Logic

Forwarding and stalling occur only when a data dependency exists. They do not occur just because a branch or load happens to be adjacent to another instruction.

Detecting lwstall

lwstall requires a load instruction to be followed by a consumer one instruction apart

After decoding both instructions (load in E, consumer in D), we detect:

lwstall =

MemToRegE # Instr in E is a load

AND ((rsD == rtE) OR (rtD == rtE)) # The consumer is using lw result

If so, we need to stall.

Detecting branchstall

Similarly, a branchstall requires a producer followed by a branch one instruction apart

After decoding, we detect:

branchstall_E =

BranchD # Instr in D is a branch

AND RegWriteE # Instr in E is a producer

AND ((WriteRegE == rsD) OR (WriteRegE == rtD)) # Branch consumes result

Special case: We also need to stall branch followed by load two instructions apart The logic is similar:

branchstall_M =

BranchD

AND MemToRegM # Instr in M is a load

AND ((WriteRegM == rsD) OR (WriteRegM == rtD ))

Combined, branchstall = branchstall_E OR branchstall_M

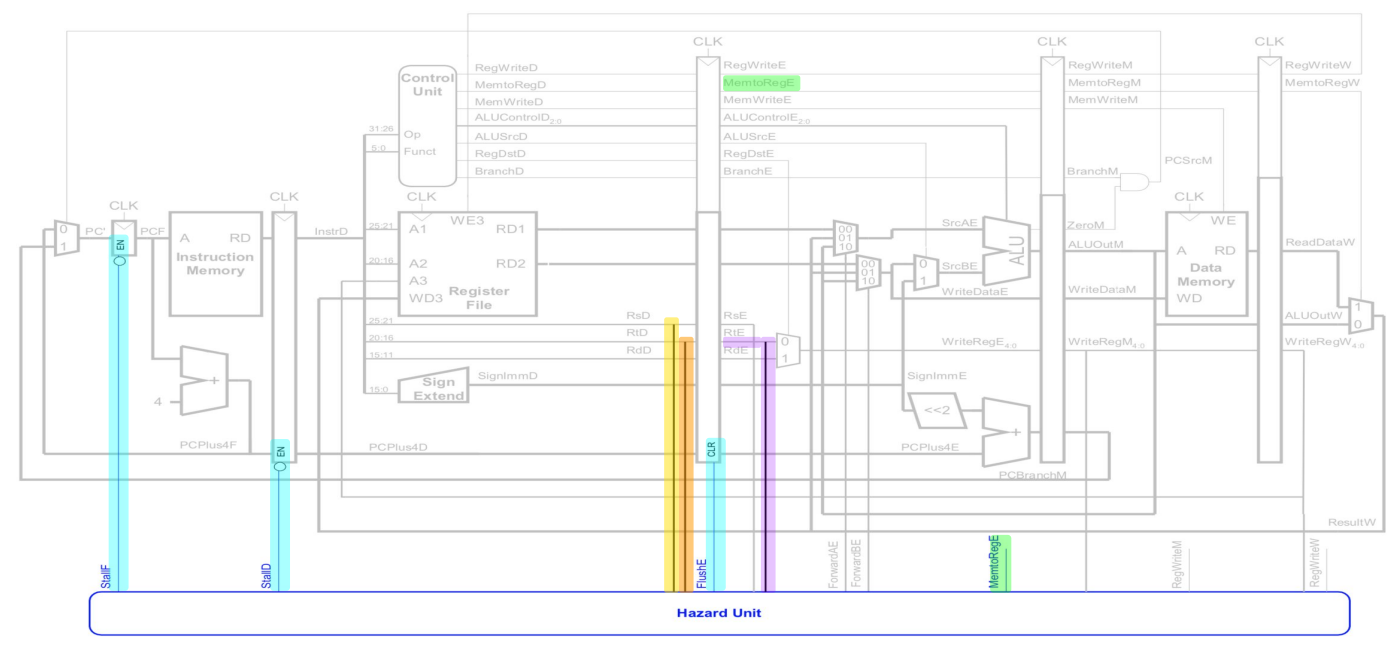

Stalling and Flushing

A stall stops the pipeline from advancing, waiting for current stages to finish

Circuit wise, on either lwstall and branchstall, we activate the following wires:

StallF: Freeze PCStallD: Freeze current instructionFlushE: Clear the already decoded operands, creating a bubble (NOP) in execution The flushed data will create a bubble (NOP), which will give extra cycles for data to become ready

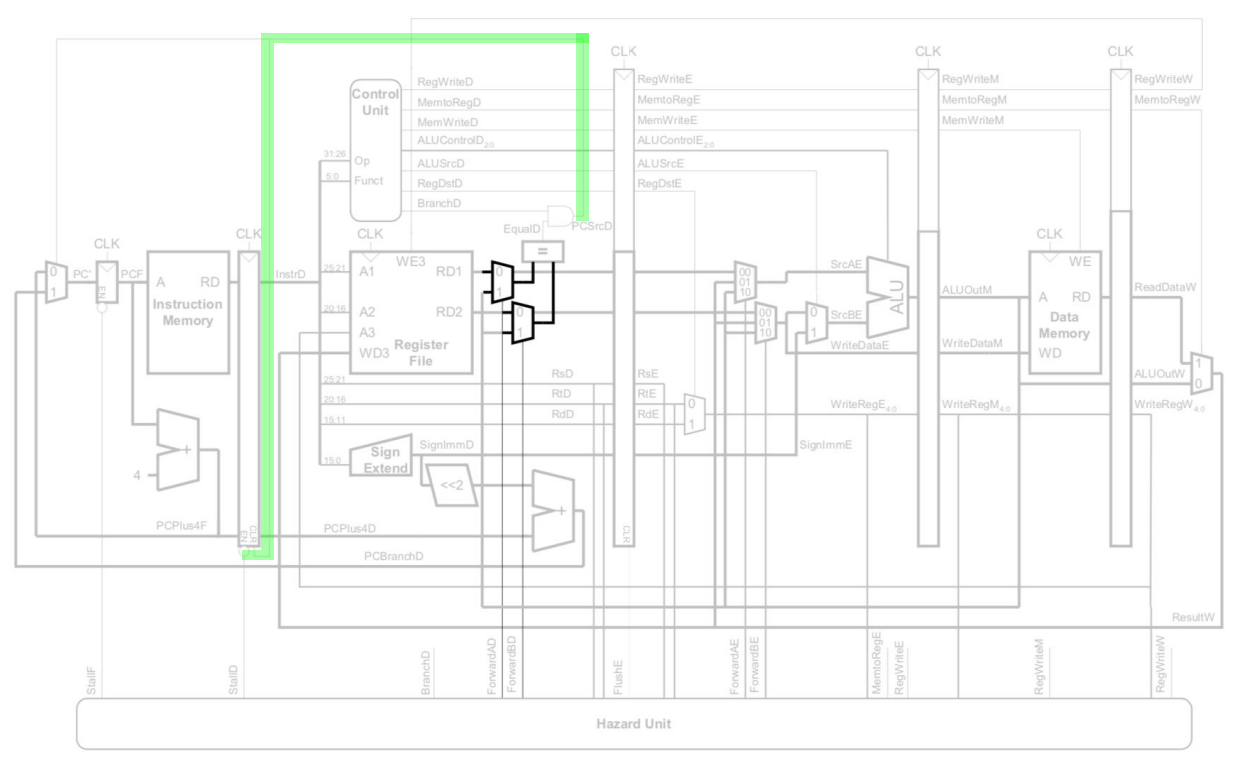

Branch Misprediction

Branch misprediction is a control hazard, not a data hazard.

The processor always assumes the branch is “not taken” and fetches the next sequential instruction. If branch is taken, it’s a misprediction.

Below are the steps:

- Resolve the branch in D using early branch logic

- Meanwhile, the next sequential instruction is already fetched into F

- If the branch is taken (misprediction), the instruction fetched in F must be flushed (

FlushD). - At the next cycle, the correct instruction is fetched again.

The flushed instruction also introduces a bubble

Examples

Suppose we have the following instruction sequence. Assume xxx, yyy, and zzz have no data dependencies.

main:

lw A, 1000

beq A, B, branch

xxx

yyy

branch:

zzz

1. Stalling

Suppose the branch is not taken. Sketch the execution trace.

2. Misprediction

Now, suppose the program starts with A != B , but after lw, A == B, so the branch will be taken.

This is a bit of of scope. My initial solution had a mistake. Sorry about that…