1-Memory

Published:

DRAM

Dynamic Random Access Memory: address -> data Content addressable memory: key -> address (Unit 3)

On PCB, DRAM packaged in DIM (Dual Inline Memory Module)

- Usually 8 chips (9-10 if error correction)

- Connected to CPU/SOC using the DDR (dual data rate) bus

- DDR: data can be transferred at both clock edges (double frequency)

- GDDR: graphics

- LDDR: low-power

- DDR5: latest standard

- Data bus width: 64 bits (32x2)

- Address bus: 21 bits (Longer addresses take multiple cycles; slow if too wide)

- Command bus: 7 bits (?)

- 64 ms refresh

- DDR Standard: JEDEC, allow different manufactures to interoperate

- In SOC, the Memory Controller controls the DRAM

- May have more than 1 MCs

- Each MC can be attached to more than one DRAM modules

- The connection DDR is a channel

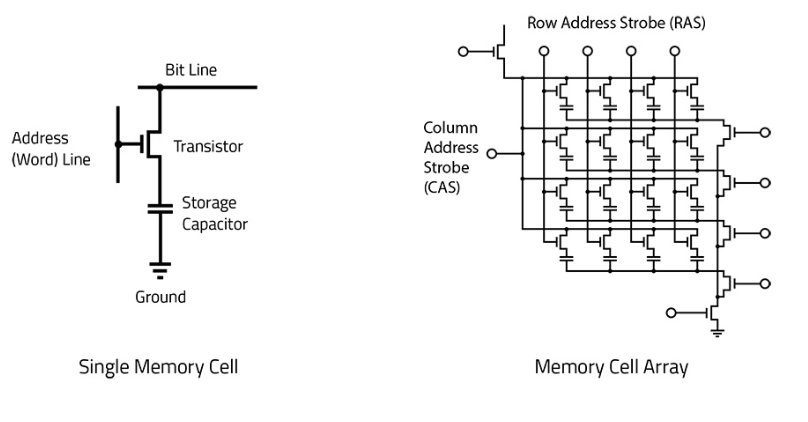

DRAM Cell

G: word line; D: bit line

Write:

- Activate word line

- bit line = value

Read:

- Activate word line,

- Discharge value = bit line -> Analog sense amplifier (amplifies to drive)

- Take output, and restore the value

Subarray

aka “mats”, square to normalize latency

- Bit line connected to sense amplifiers

- Address -> decoder -> word line cell -> subarray -> mat -> sub-bank (~4) -> bank -> chip -> rank -> channel -> DIMM

Bank groups (BG0-7) on a DRAM die

Page buffer in one bank: sense amplifier that holds a data row

- Each row can be as wide as 8K

- Refreshing can happen concurrently (other banks can be refreshed while one is read)

- Any command from processor is broadcasted to all dies

E. DRAM bus runs at 2400 MHz. What is the peak bandwidth between the memory and the SoC?

- 2400 * 2 * 8 bytes (maximum)

Don’t forget to x2

64-bit: 8 byte per transfer

Commands

REFRESH

- \(t_{REFI}\): maximum supported refresh interval (~4000 ns)

- Limits the peak BW

- \(t_{REFC}\): blocking time for refresh per row (~200 ns)

- E. about 95% BW available

READ

ACT(activate row): drop all data to the bottom buffer on the bank- Energizes a particular wordline for subsequent access

- \(t_{RCD}\) (row-to-column delay) from

ACTtoCAS

CAS(column select)- \(t_{CL}\) (column-read delay) for data to be read out

- Data bursted out then (bursted out in group of 16 (burst length))

PRE(precharge): so the nextACTcan happen- Precharges the row to \(\frac {V_{DD}} 2\) to drive the sense amplifier

- \(t_{RAS}\) (row-access strobe delay) between

PREto the nextACT - If reading a different row in the same bank, \(t_{RP}\) (row-precharge)

- Not necessary if reading the same row

Error

Soft Error Prone to particle strikes (E. \(\alpha\)), may trigger bit flips

- Want detect and recover

- Store data redundantly (E. 2x to detect, 3x to correct)

- ECC (E. 2D parity)

Hard Error DIM-SOC bus line stuck at 0 all the time

Failure model

FIT: failure of 1 GiB of memory per 1 billion hours of operation

- ~15 for memory

- ~100 for GPU memory

SECDED: correct 1-bit faults, detect 2-bit faults

- Typically done in 64-bit chunks Chip kill: make sure still works if one chip in DIMM fails

Correction Scheme

TMR (Triple Modular Redundancy): give 3 copies to have a majority vote

- Very cumbersome (3x load latency + comparison; 1/3 capacity)

- Can correct any number of bit faults

Error Correction Code

- Sometimes black box

- Support errors in the check bits

- Data \(d\) (E. 64 bits) + check code (E. 16 bits)

- Multiply \(d\) by a constant \(m\). Store \(dm\) in memory

- When retrieving, divide by \(m\). If no remainder, good;

- If there’s a remainder \(r\), we know which bit to flip

where \(k\) is the position of the bit flip To correct,

\[\frac{d'}m = \frac{d\times m}{m}\pm \frac{2^k}m\]Need to find \(m\) such that \(\frac{2^k}m\) produces unique remainder for all \(k\) (E. 243)

- Constraint on \(m\): minimize the number of check bits

- For double error detection, you get a remainder that matches nothing

Error Correction Scrubs (ECS)

Error accumulate over time so you can’t correct

- Solution: scrub memory periodically

- Error correction happens in the memory controller: Need to read + write from the chip

- Also a blocking operation

DDR5 only does SEC (no double-bit) (Q: is it required on thei chip, or ???)

Random Access Strobe timing

\[t_{RAS} = t_{RCD} + t_{CL} + t_{RP}\]E. DDR5 memory, 1 DIMM on the system, 8 GiB, no ECC, clock 3000 MHz. Estimate the latency of 2 successive (back-to-back) reads to two different rows in the same bank

- 8 chips on the DIMM, each with 8 Gib of memory; to output 64 bits of data

- \[t_{RCD} + t_{CL}*n + t_{RP} + t_{RCD} + t_{CL}*n\]

- Multiple \(t_{CL}\)s that reads burst of data

- No need for last recharge E2. Same condition, but to the same row

- \[t_{RCD} + t_{CL}*n + t_{CCD} + t_{CL} * n\]

- No need \(t_{RP}\) twice

- \(t_{CCD}\): column-to-column delay E3. Two different banks E4. Two different DIMMs

- …

Cache

Speed limited by memory

- Even worst due to instruction fetching (same time as memory access)

- Store these locally within the SoC in faster memory -> cache

SRAM

Bistable element, with charging capacitor on each side

- On die

- Same process technology for memory as with CPU

- Planar CMOS, trench capacitor

Hierarchy

- CPU

- L1I, L1D (L1I -> CPU -> L1D pipeline)

- L2

- L3

Main memory Each layer has ~10x capacity & access time

- Temporal locality: loop

- Spatial locality: array

Physical organization

2D array

- Line (block) size: 64B

- x # of cache lines Address -> decoder -> tag array -> data array

When caching address, tag address = x « $log_2$(cache line size)

Associativity

- Direct mapped: one addresses only map to one index

- Set associative: one address maps to a set of indices (aka ways). May be in either of it. Decoder checks if either tag in the ways

- If hit, extract address offset

Policy

Evict policy

- Random

- Least recently used item (LRU)

- Most recently used item (MRU)

- OPT: relying on a oracle knowledge

- Adaptive (based on ML algorithms)

Store policy

Hit

- Write-back: only update L1, mark line dirty

- Write-thru; Update propagate to higher levels (L2, L3, …)

- Simple coherence

- Slow Miss

- Write allocate: bring data to cache and write

- Useful for

calloc() - Good temporal locality

- Works well with writeback

- Useful for

- Write around: skip level you miss. Update the level where data hits

- Useful if no further reuse (E. logging, stream media,

free())

- Useful if no further reuse (E. logging, stream media,

Between levels miss (level specific):

- Inclusive cache: $level_x \subseteq level_{x+1}$. Store in all intermediate level

- Exclusive cache: a cache line exists uniquely in one level.

- aka victim caching (evict to next level)

- NINE: neither, no commitment, in-between

MSHR

Performance optimizations for loads

LD x

LD x+4

LD x+8

LD x+12

Suppose x misses in L1D. Cache Controller issues to L2

- While L2 is accessing

x, processor looks forx+4- Wasteful here to issue another miss for

x+4 - Processor fold subsequent misses to the same pending cache line This is called MSHR (Miss Status Handling Registers). Tracks all pending misses

- Wasteful here to issue another miss for

- Table of missed addresses, corresponding to PC of all subsequent loads

- One table for each level of cache

HW Table has limited size of the number of addresses, and the number of PCs for each address.

- If no space, stall CPU (no folding available)

Write Buffer

Performance optimization for store misses

st x

st x+4

...

Buffer up the stores in a write buffer (mini cache with addresses and 1 line data)

- Once filled, evicts and sends to the next level. If you load the same address as stored, data forward directly from buffer

Example

Q: How many lookups happen in L2, and how many writes go to the DRAM? L1D MSHR: 4 entries

miss[3:0], each can handle 16 misses Suppose load 32K ofints, 64B cache line size

- First miss instance is stored in a cache line

- Subsequent misses on the same line are buffered (folded)

- For L2 layer, need 32K / (4 * 16) = 512 cache line lookups

- Without MSHR, 64x more

- 16 * 4 due to 16 fold * 4 bytes for

int

- Exact same as L1D line size, since

intis the most common- Every 16 misses are collapses into one L2 lookup

L1D store buffer: can combine consecutive writes to 1 cache line

Suppose store 16K

ints, 64B cache line size

- If L1D store miss, send to L2, but not individually

- Write buffer collects every write into a single cache line

st c[15:0](forint)- When line filled, send the request to L2 to write

- Without store buffer, L2 4096 writes * 4 byte

- With store buffer, LL2 4096 / 16 = 256 writes * 64 bytes

- Same data, but less metadata (location, write size, etc.)

- In L2, still write allocate system -> all misses -> send to DRAM

- No additional merging possible. All misses are cache line size

- If you alternate cache writes,

st c[i]; st d[i], store buffer will be useless due to conflict

DRAM traffic

- Memory Controller (MC) that receives all miss traffic from SoC. Makes request (

PRE,ACT, column R/W) to DRAMAssume

- 16 GiB DIMM

- 8 Bank groups (each DRAM is x8, also sending 8 bits of data)

- Each BG has a row buffer

- 8 open rows per DRAM

- 64 open rows per DIMM

- 4 sub-banks per bank group

- 2 subchannels per DIMM

- Miss traffic trace

- Assume no code misses. Data only

- Reason from L2 output

read A[0:15]

read B[0:15]

// still stuck here, but processor will keep requesting

// non-blocking write

read A[16:31]

read B[16:31]

write C[0:15]

Q: How should PA -> DRAM address mapping be set up to improve parallelism

- Make sure

A,B,Cneed to be written to different banks concurrently

- If same bank, blocking each other. Won’t need to issue separate open and close

- E. BG0 has slice of

A, BG1 has sliceB- When MC controlling cache line requests into DRAM commands, process out of order

- Readings are more critical. Make it happen before the write

- Instruction page > read > write

- aka memory scheduling

Cache causality

Reason of misses:

- Cold (compulsory): first reference

- Capacity: too small (even if fully associative)

- Conflict: addresses map to the same cache line

- Assume cache is infinitely large and fully associative

- Any miss will be cold -> label them

- Solution: pre-load all data into cache (prefetch)

- Hardware prefetcher (ML-based)

- Also increase block size

- Finite capacity, FA

- Misses: cold + capacity

- Solution: increase capacity

- Finite capacity, SA/DM

- Will have everything

- Subtract the previous two out -> conflict misses

- Solution: increase associativity

- change cache indexing (hashing function)

- change replacement policy

- Capacity -> latency

- Block size -> latency (but less extent)

- Associativity -> latency

Fully associative structure

CAM: content associative memory

- (tag, data) pairs

- Search the tag in parallel in every row. If match, data out.

- Typically 1 clock cycle

- Number of items searched in 1 cycle: search scope of a scan

- XNOR check every bit of the tag -> every bit ANDed

- The key bits are broadcasted to every cell -> latency increases very rapidly

PORT

How many R/W can do to a given memory at a time

- E. 1R1W; 1RW; 2R1W

- 1RW: standard SRAM array. Only one address (wordline) you can energize

- 2R: additional wordline and bitlines attached to every cell. Two sets of sense amplifiers. To transistors controlling the read -> more latency

Example:

- RF: 2nR, nW (n is the number of concurrent instructions in-flight)

- L1: 2R, 1W

- L2: 1RW

HW1

clflush(ra): evict from cache block. If cache line is 64 bytes, need to do for allra % 64rdtsc: timer, issued before and after- Need to serialize the instructions

- Use

rdtscp - Or insert

cpuidjust before therdtsc lfence

mfence: prevent multiple CPU cores to interact with memory at the same time Noise reduction techniques:- Pin process to specific cores:

taskset - Pin certain page for DRAM:

mlock

Virtual Memory

Very large linear array, abstraction. Allow portable code

- 0 to \(2^N-1\).

- The next location is previous location + 1

- Not all physically addressable

Caching

How to provide such VM illusion Physical memory = populated DRAM (~GB) + size of swap space (E. SSD, HDD, tape ~TB) Solution: cache VM chunks into physical memory Raises a few questions

- Block size? page size (OS page size, not to be confused with DRAM row buffer size)

- In modern OS, 4 kB, 1 MB, 2 MB, 1 GB

- Associativity? fully associative

- When

malloc()called, a chunk is allocated and mapped to the DRAM page- Allocates anonymous data. Not stored to hard drive

- After certain

malloc()s, DRAM fill out. Moved to swap space - If swap space also fills up: Out Of Memory (OOM). Can no longer illusion

- For file-backed data reading, resides on non-volatile storage

- Placed in DRAM page cache when read

- If miss in DRAM, swap space fetch cost is very expensive. Associativity reduced conflict misses.

- Search is done in software (OS)

- Can’t do FA for lower-level cache, since hardware algorithms for searching data can’t execute in ns.

- When

- Eviction policy?

- Store hit policy? exclusive between swap space and DRAM

- Except page cache in DRAM is inclusive (caches hard drive files)

- Flush command pushes page cache to hard drive

- For anonymous data, DRAM is the final destination

- Except page cache in DRAM is inclusive (caches hard drive files)

- Store miss policy? write allocated to DRAM

This is called software managed cache

- Replacement in SW (higher latency)

- Fully associative

Page Table

Data and metadata (ana tag)

- Page address

- Permission (rwx)

- WC (does it support multiple consecutive writes)

- UC (uncacheable)

- User/kernel Need to know which pages are present in DRAM + Swap

Data structure: page table Need to

- Locate item quickly (E. n-ary tree)

- allocate/deallocate pages

- Small in size

Page walk

aka search through the tree for address translation

- Implemented in HW or SW

E. if tree has 5 levels, need 5 reads to get a memory address.

TLB

Cache page walks -> Translation Lookaside Buffer

- Special cache for VA -> PA pairs

- Same level as L1

- One page walk done, cached to TLB

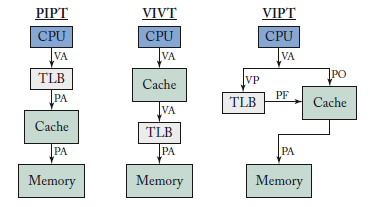

VM cannot be directly mapped to cache, since different programs will have different VA. Need to first translate to PA

- Can directly translate if sure that PA not used by any other addresses Program -> VA -> PA (page walk, TLB cached, else expensive) -> cache

- TLB latency + cache latency

- 50% overhead :(

VIPT

Optimization: given VA, lookup in TLB and cache concurrently

VIPT caches (Virtually Indexed Physically Tagged)

- Virtual address to compute index

- Physical address to check tag

- Need VA -> PA to conserve index & offset bits

- \(log_2\)(page size) = index + offset bits

Translation overhead

- PA only: embedded system

- If you know exactly how many processes the system has.

- No dynamism

- Page table

- High radix structure (tree) to optimize the search

- 4-5x overhead!

- Cache VA -> PA translation in TLB

- Virtual page number -> physical page number

- Only pay cost once

- TLB is fully associative, since misses are very expensive

- VIPT: hide TLB lookup latency under cache latency

Virtual page number cache index cache offset

Optimizations

Cache size limited by page offset bits. Suboptimal Solution: make cache set associative, so each index can store multiple tags

- Allows larger total cache size for same index bits

- If TLB miss, raise an exception (TLB fault), handled by OS or hardware microcode

- Page walk, and fill in TLB

- Build HW caches for each page walk level (again)

- Known as MMU caches

- If no translation exists (first-time access): page fault

Example

Virtual -> physical -> cache -> DRAM

int *a = malloc(4096 * sizeof(int)); // dynamically allocated

// same for b and c

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

Suppose 64-bit VA space, 40-bit PA space -> $2^{40}$ max DRAM capacity

- OS page size: 4 KiB

Max page

- Max working set size (data only) = 3 * 4096 * 4B= 48 KiB -> 12 page table entries

malloc()will align to page entries.aligncompiler command

Physical Config

Suppose:

- L1D: 64 k, 64 B lines x 64 sets x 16 ways

- L2D: 256 KiB, 64 B lines x 16k

- L3: 8 MiB, 64 B lines

- Writeback for hit, write around for miss

- 4 KiB page size

- VIPT

Q: What is the size of the L1D tag array, assuming a VIPT cache - Page size = 64B x 64 sets = 4K - 40-6-6=28 bits of tag (use physical size) for each line - Total: 28 bits * (64 sets * 16 ways)

- Assume a FA, 16-entry TLB

- TLB is 1 valid bit + VPN tag + PPN tag

- Size of one entry = 1 + (64-12) + (48-12) = 69 bits

- If TLB includes the bits used from MRU replacement,

- 4 bits of index for MRU entry, 4 more bits

- If include LRU replacement,

- 4 bits for each MRU entry, 16 more bits

- OR a matrix with comparison bits for each entry: 16 * 15 / 2

- More data, but simpler comparison algorithm

Code Optimization

To improve locality E. A 2D (byte) matrix is laid out linearly in memory

- Load The bae address

- Add offset (0)

- Store this address to somewhere else in memory With cache (E. 4-entry, FA cache, line size: 4B, writeback on store hit, write allocate on store miss)

Suppose transposing a matrix, row accesses will hit, but column ones will miss

- Memories are in row-major order, so the columns will miss!

- Change how arrays are accessed, and increase

- Fetch a square block of data into the cache -> Cache blocking

- Set up loop index, so the amount of data accessing fits into the cache size